Who Is Rising? Popular Critiques of the Economic Power of Mega-Churches in Ghana

“They say ‘Africa is rising’. But I think it’s only the politicians and pastors who are rising”, said Kodjo, a friend of mine who worked in the financial sector in Ghana’s capital Accra. At the time of talking to him in March 2019, I was in Ghana to do fieldwork on a banking crisis that had resulted in the collapse of nine local banks. After nearly a decade of the proliferation of Ghanaian-owned private banks, which had given an impression of a robust, “rising” private sector, in 2018, many of these new banks became insolvent and were taken over by state-owned banks. Numerous finance professionals lost their jobs while ordinary bank depositors struggled to get access to their savings. It was thus a moment when Kodjo was perhaps particularly critical of the narrative of “Africa rising”, although he was among what has been widely termed the “rising African middle class” with a professional career in finance. He challenged the listener to be more specific about what and who has been rising in Africa in recent decades.

While the popular critique of politicians and their practices of wealth accumulation is well-established in public debates and academic scholarship on African politics, in recent years, Christian pastors have become subject to a similar line of critique. Kodjo’s comment about “pastors rising” draws attention to the increasing political economic role of Christian religious leaders and churches in sub-Saharan Africa. Christian pastors have become part of the established elites in many African countries. To make sense of who, precisely, is rising is thus an essential aspect of understanding the new kinds of actors who are wielding political economic power in Africa in the 21st century.

The past 30 years have seen a growth in the popularity of the Charismatic Pentecostal variant of Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa. One visible manifestation of its popularity is the rise of Charismatic Pentecostal mega-churches in urban areas, which underpins the political and economic influence of Christian actors in Africa. The first point to underscore in this regard is that Charismatic Pentecostal churches have been incredibly successful at building institutions. The “mega-church” is a global model, which originated in US evangelical culture. It stands for an expansive Christian organisation that has a large branch network and that is growth-oriented. These churches are also very structured organisations, with financial, PR and HR departments, which means they have become significant employers in many African countries. They are also often architecturally impressive physical infrastructures that have been literally “rising” in the eyes of ordinary city-dwellers.The “mega-church” is a global model, which originated in US evangelical culture

Another reason for the rise of the mega-church lies in Pentecostalism’s encouragement of active participation in church life. Ordinary church members typically volunteer their labour and give money and other material resources for advancing the church’s evangelical cause, to win more souls for Christ. For instance, it is common for church members to pay a tithe, namely 10% of their monthly income, to the church community, and volunteer many hours of labour per week to serve in diverse committees and church events. Additionally, West African mega-church headquarters receive large volumes of remittances from their branches in the African diaspora in Europe, the US and also parts of Asia, aiding their institutional expansion.

As one result of their expansion, Charismatic mega-churches and their leading pastors hold influence way beyond the domain of “the religious” – they have become important actors in the national economy. For example, in Ghana, mega-churches have accumulated capital resources, which circulate in local economies through different formal, and informal, channels. Pastors have become trusted business advisors thanks to their success at building institutions. Many pastors serve on corporate boards and advise entrepreneurs on how to build a business. Another aspect of their economic role is their investment of church capital in diverse types of urban ventures; currently, more research is needed on the kind of material effects that such investment activities generate on the ground, and who or what may be rising, concretely and figuratively, as a result of such church-led financial activity.“Africa Rising” is a global catchphrase of which one purpose is to convince global capital markets of Africa’s investment potential

When writing this piece in March 2024, popular critiques of the perceived “rising” economic potential of the country have become even more pronounced in Ghana, which finds itself in the midst of a prolonged post-COVID economic crisis. Many Ghanaians aside from Kodjo might agree with the anthropologist Janet Roitman, who has argued that “Africa Rising” is a global catchphrase of which one purpose is to convince global capital markets of Africa’s investment potential. The “rising African middle class” is part of this grand narrative, which may serve the interests of capital rather than the interests of those who might aspire to be part of this middle class. At the same time, it is important to understand how ordinary people, from professional experts to informal sector sellers, themselves engage with the very narrative of “rising Africa”, and make acute observations on who or what is rising, and who is left wanting.

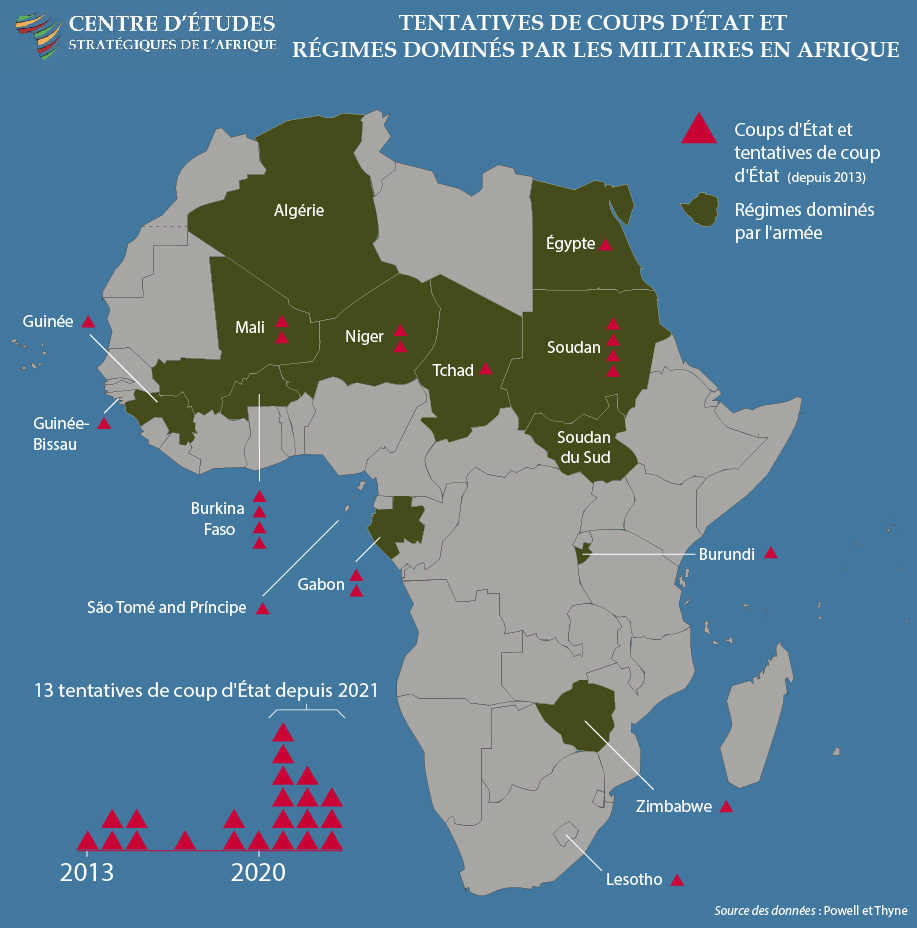

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

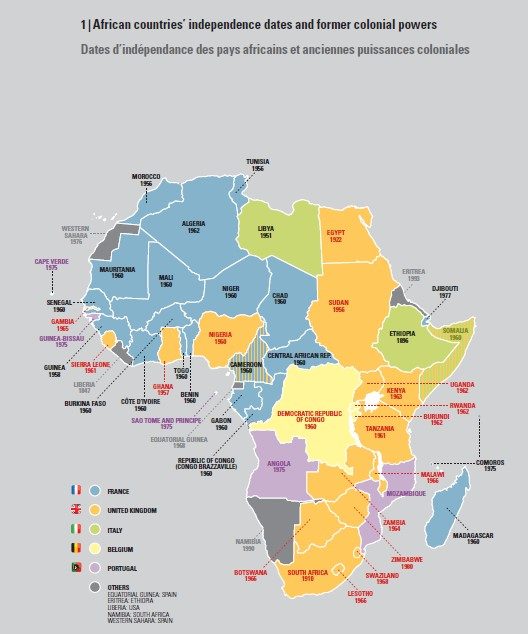

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

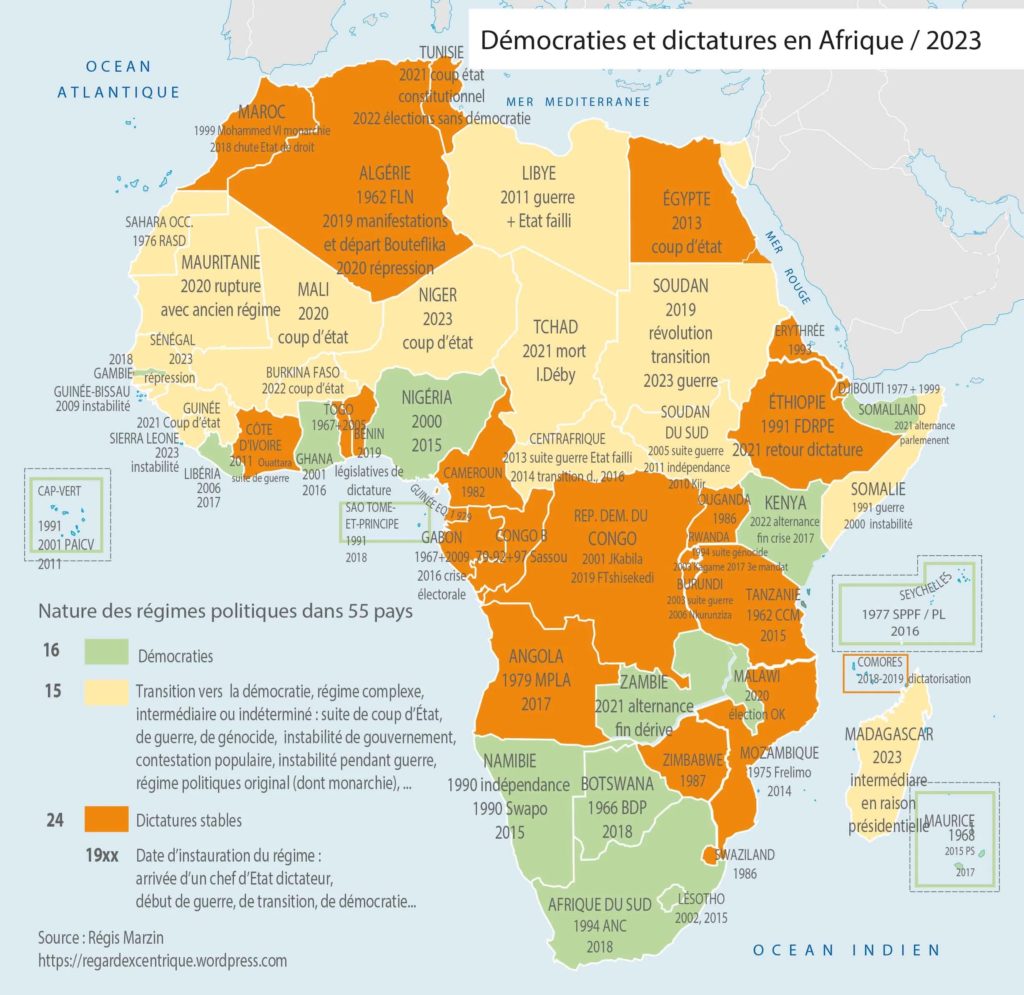

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

VIDEO | The Challenges of Demographic Trends in Africa, with Dêlidji Eric Degila

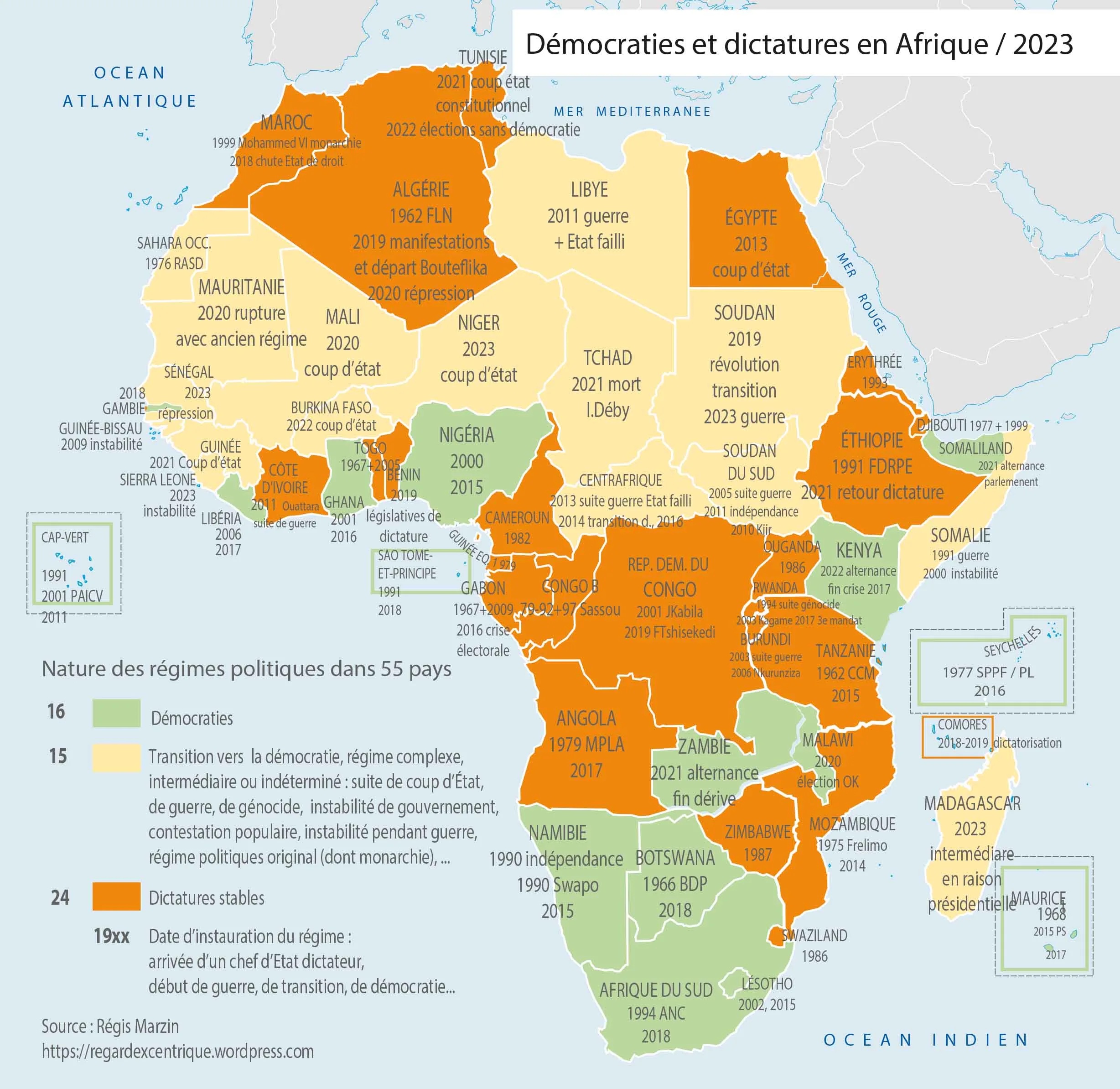

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

PODCAST | Ken Opalo on the Prospects of Democracy in Africa

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.

VIDEO | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa, by Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou

Geneva Graduate Institute

VIDEO | Africa in a 2030 Perspective, with Lord Mark Malloch-Brown, former Deputy Secretary-General of the UNDP

Geneva Graduate Institute

DOCUMENTARY | Missing Dollars: How Illicit Financial Flows Affect Developing Countries

Geneva Graduate Institute