African Conservation Futures

The colonial roots of biodiversity conservation are clear to read in the historical record. Game reserves were established in the South African Cape in the 1880s to protect animal populations targeted by European hunters, and were soon copied in the German colony of Tanganyika and British Kenya. By that time the first, and most famous, national park had been created in the United States, at Yellowstone (1872). The first US parks were created on expropriated land by a government that saw nature in terms of an unpeopled wilderness, symbolic of the settler nation. The US claimed vast areas of land from which indigenous inhabitants had been cleared – some were set aside for conservation.

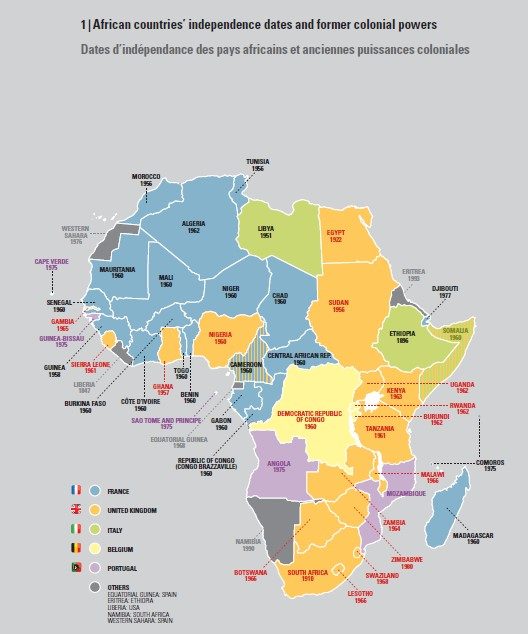

Euro-American ideas of parks to preserve nature from human settlement were soon copied, especially across the British Empire (Australia, Canada and New Zealand by 1894), as well as in Europe (e.g. Switzerland in 1914). In Africa, the first national park (the Parc National Albert) was created by royal decree in the Belgian Congo in 1925, closely followed by the Kruger National Park in South Africa in 1926 (named after a famous white Boer leader).

An International Congress for the Protection of Nature was held in Paris in 1931, followed in 1933 by an intergovernmental conference held in London proposing national parks. Colonised nations were not invited. After the Second World War, as the prospect of decolonisation loomed, more national parks were declared in Africa – for example Nairobi National Park in Kenya in 1946 on the edge of the rapidly growing city of Nairobi, Serengeti in Tanzania and Murchison Falls in Uganda in 1951.

Postcolonial Conservation

You might expect the governments of independent African countries to have abandoned such examples of blatantly colonial and Euro-American ideas about nature. Far from it – the creation of protected areas boomed in Africa, as elsewhere. The area protected globally more or less doubled over the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Why were colonial models of conservation retained? Historians suggest that national parks appealed to governments as part of the project of modernity, and as a way to build a sense of national identity in countries whose arbitrary boundaries reflected colonial détente rather than precolonial cultural or political identities. The geographer Roderick Neumann put it neatly in 2004: “The wild areas of national parks and reserves, as products of the creation of the modern nation state, are as much an expression of modernism as skyscrapers.”

It was also believed that national parks could support national economic growth through a tourist industry. Tourism had been central to the success of the US parks, and the model was copied enthusiastically in Africa. In 1952, the first scheduled flight by jet airliner landed in Entebbe, en route to South Africa. Within a few years, global package tourism had begun, with African national parks underpinning the extensive commercialisation of wildlife.

Certainly, conservation thrived in postcolonial Africa. And the priorities of national development justified population displacement to create national parks in very much the same way as they did for projects such as dams, industries or agricultural schemes.The priorities of national development justified population displacement to create national parks in very much the same way as they did for projects such as dams, industries or agricultural schemes.

Today, there is no single set of ideas across Africa about how conservation should be done. In some countries (Tanzania or South Africa, for example), conservation budgets depend on income from sport hunting (as do communities in many countries, as under the CAMPFIRE Programme of Zimbabwe), while in others (Kenya for instance), all hunting is banned.

Of course, everywhere, government-designated protected areas still dominate the sector. Ambitious global targets for protected lands and seas (30% by 2030 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework of 2023) suggest protected areas will continue to expand, but they may have to change. Conservation corridors such as the Selous-Niassa corridor in southern Tanzania attempt to combine wildlife and people, but are controversial. For critics, conservation authorities show an appetite for land and disregard for the rights of rural people that resembles a hangover of colonial governance.

Alternative Conservation Models

But there are other models. Many countries (Zimbabwe or Namibia for example) have extensive community-based conservation programmes. In Kenya, wildlife “conservancies” range from large private estates to community-owned and controlled areas. A number of countries are experimenting with public-private partnerships, such as that with the international NGO African Parks, which manages 21 protected areas in 14 countries. There are also numerous experiments with market-based approaches to conservation, from “Rhino Bonds” to carbon offset payments.

Africa is not one place – there are many different countries, with different histories. Outside influences still intrude (the popular Western anguish about hunting for instance), and international debate about African wildlife is amplified by globalised social media.African governments recognise the importance of biodiversity loss as a crisis alongside climate change and numerous other serious challenges, not least poverty and inequality. African governments recognise the importance of biodiversity loss as a crisis alongside climate change and numerous other serious challenges, not least poverty and inequality. Many different strategies are being tried across Africa, and there are examples of respectful partnerships with local people to challenge more militaristic approaches. African conservationists are innovative, passionate and bold. The future of conservation in Africa will be shaped by the willingness, and capacity, of people across the continent to find space for wildlife.

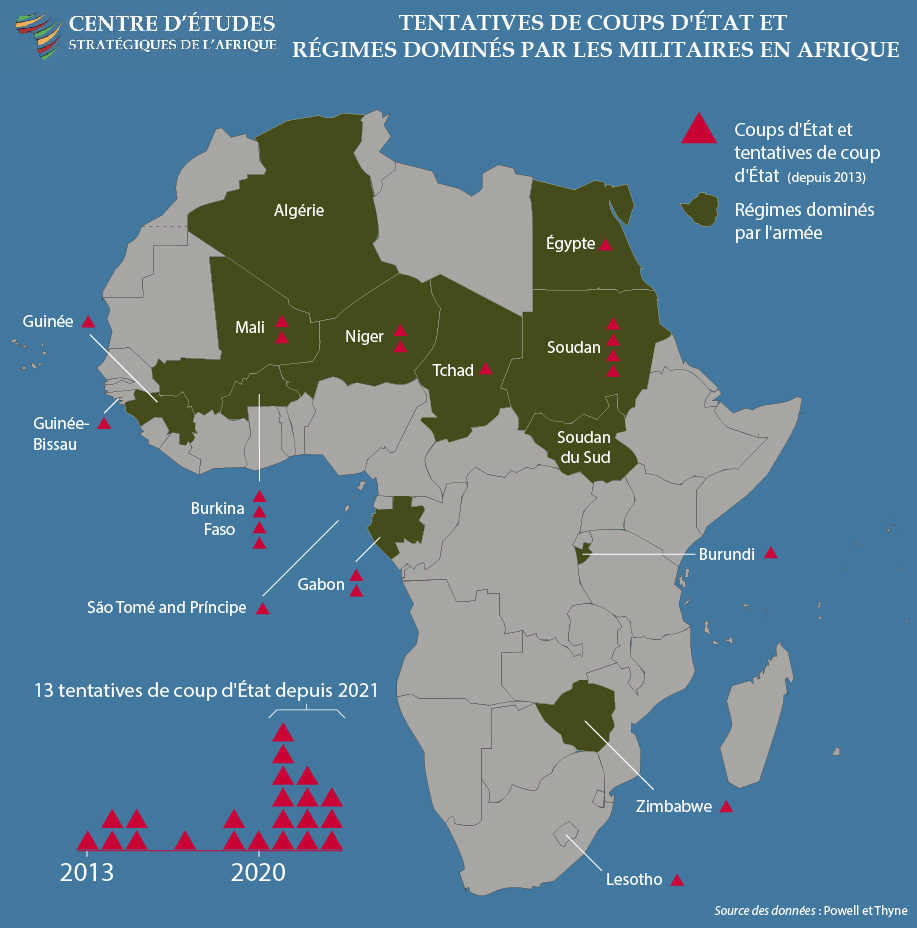

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

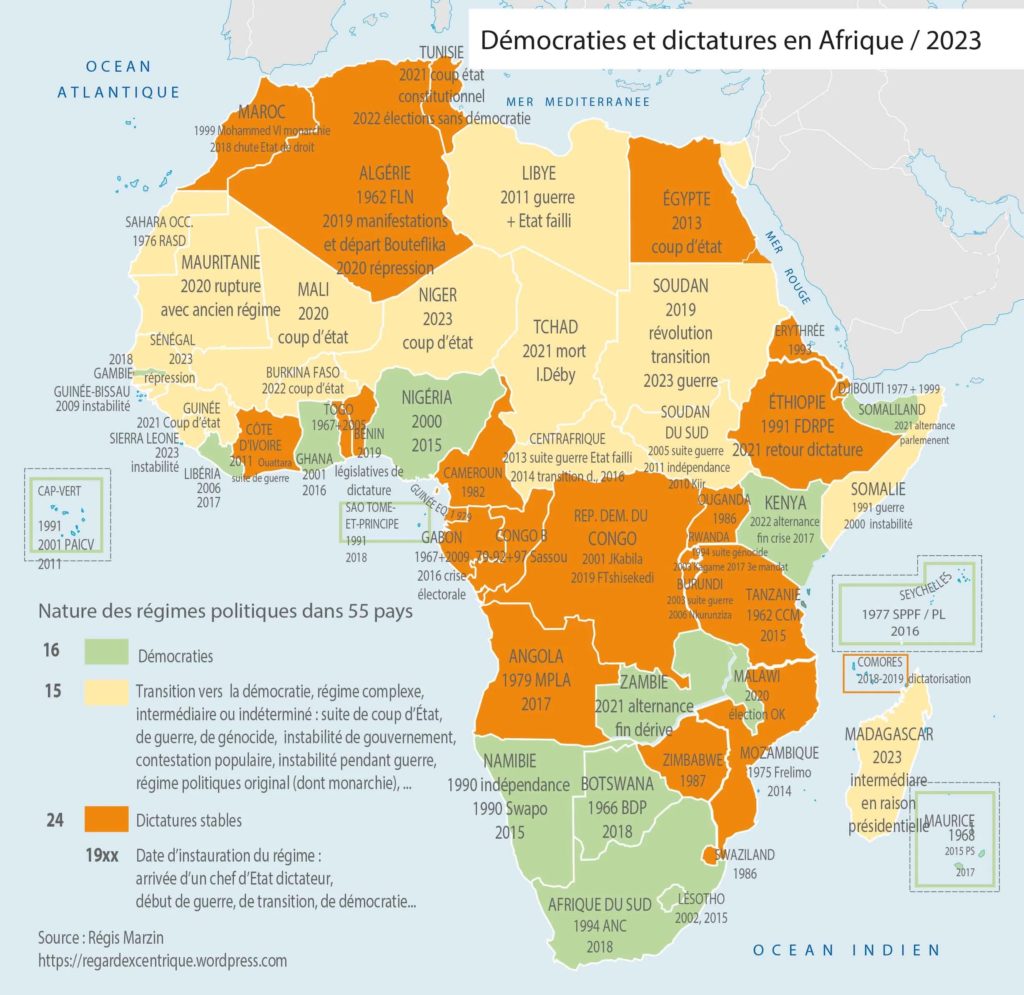

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

VIDEO | The Challenges of Demographic Trends in Africa, with Dêlidji Eric Degila

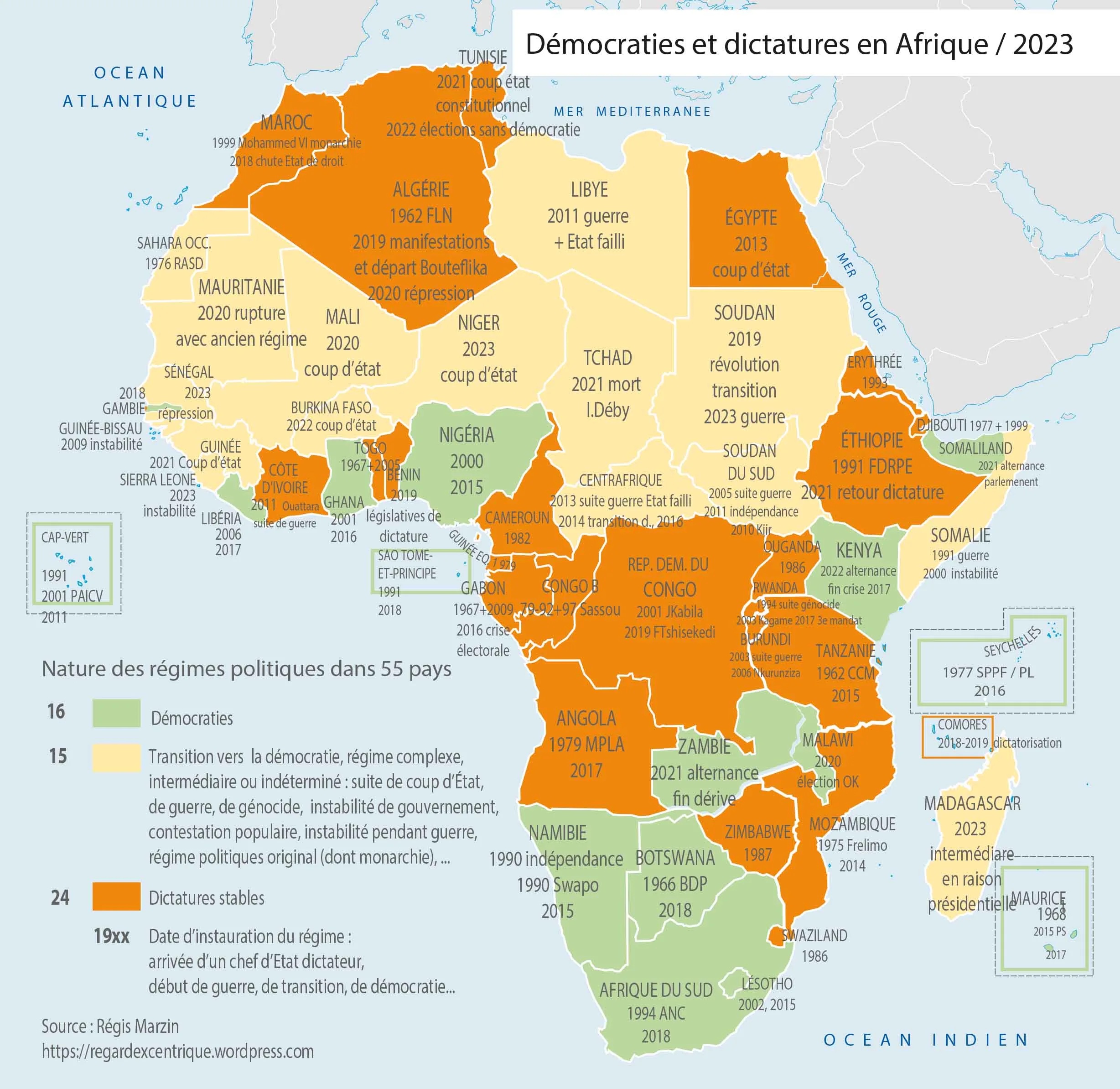

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

PODCAST | Ken Opalo on the Prospects of Democracy in Africa

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.

VIDEO | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa, by Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou

Geneva Graduate Institute

VIDEO | Africa in a 2030 Perspective, with Lord Mark Malloch-Brown, former Deputy Secretary-General of the UNDP

Geneva Graduate Institute

DOCUMENTARY | Missing Dollars: How Illicit Financial Flows Affect Developing Countries

Geneva Graduate Institute