“An Epidemic of Coups d’État” in Africa

What explains the recent surge in coup-making in sub-Saharan Africa? Can it be attributed to the birth pangs of the continent’s developing but flailing democracy? Or is it simply because the continent, as some would describe it, has never successfully consolidated its democracy in its postcolonial history?

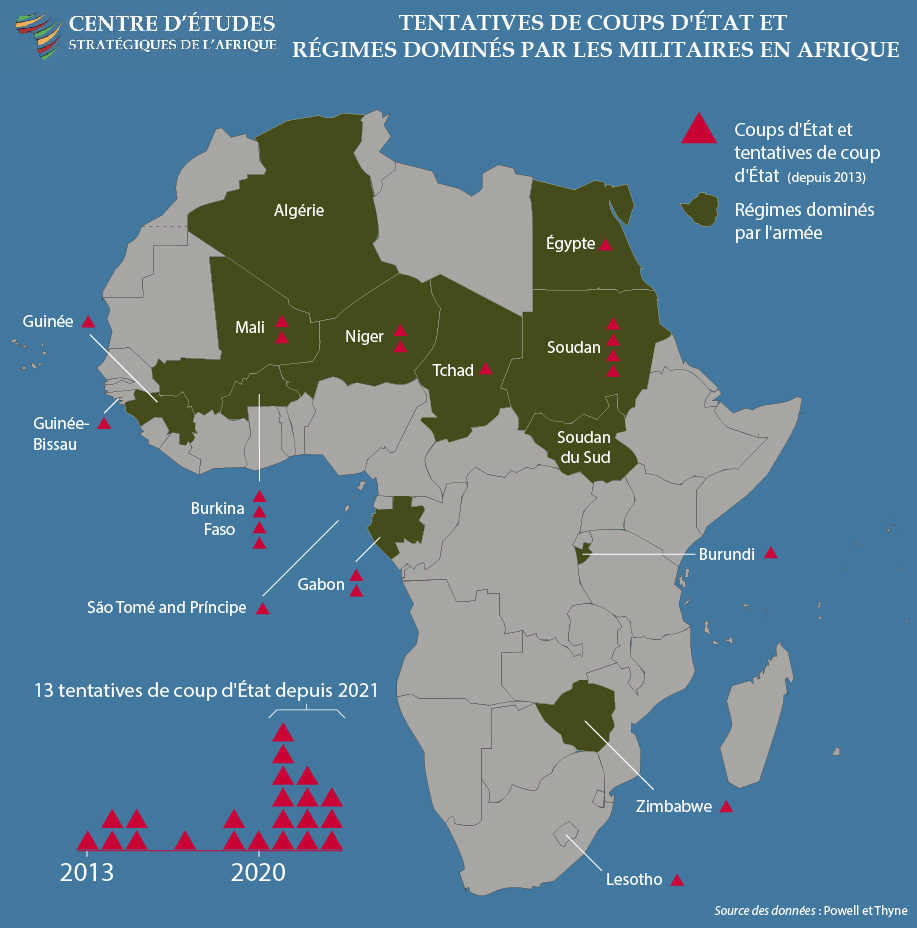

The period between August 2020 and August 2023 saw a new wave of coups in Africa (the “first wave” took place between the 1960s and the 1990s – see Box “A Brief History of Coups in Africa”). The first coup occurred in Mali in August 2020, followed in March 2021 by a failed coup attempt in Niger. In April 2021, Chad’s president was slain on the battlefield while resisting an encroaching band of rebel forces. In May 2021, Mali, nine months after its coup, experienced a putsch, followed in September 2021 by a coup in Guinea. In October 2021, Sudan experienced a coup by its top generals, prompting the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to lament “an epidemic of coups d’état”, calling upon the Security Council to stem the situation in Sudan. Since then, more coups have occurred – in Burkina Faso (January and September 2022), Niger (July 2023) and Gabon (August 2023). In most of these coups, civilians celebrated with soldiers in the streets, redolent of bygone eras when pro-military sentiment accompanied coups in many parts of the continent.

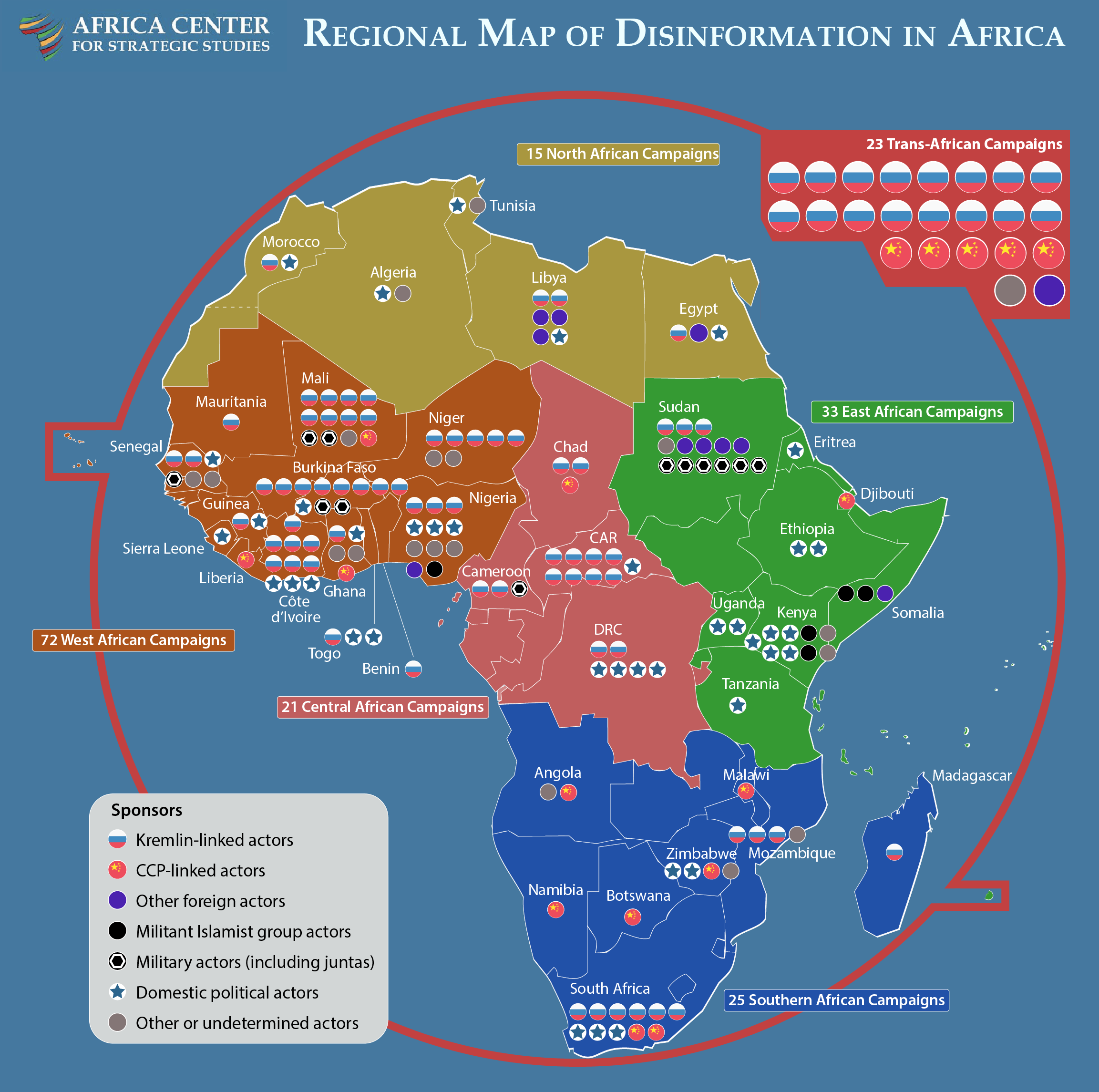

Commentators and critics have questioned whether these successive coups over a short span are the product of an inadequacy of democracy on the continent or reflect the Africans’ disillusionment with the failed promises of democracy (see Box “A Brief History of Democracy in Africa”). Besides, the failures of nascent democratisation in Africa’s early decades of independence intersected with Cold War superpower politics, monumentally deepening internal disaffection and creating the conditions under which coup-making juntas rode to power (see Box “African Politics during the Cold War”). During the Cold War, both the Eastern and Western blocs held an immense capacity to offer and withhold the technical and financial assistance that the newly independent countries desperately needed. But they could also do more! They could also sponsor coups to ouster non-compliant and disloyal regimes.

It is also worth noting that Cold War politics intersected with a legion of domestic factors that created internal disaffection and grievances about the misdeeds of Africa’s political leaders, ultimately providing the impetus for some of the first wave of coups. These factors include corruption, nepotism, patronage politics, incompetence, mismanagement of state resources, personalisation of power, and the abuse of citizens’ human rights by those in power. Numerous leaders refused to leave power after losing elections; some amended the constitution illegally to extend their tenure, while others even handpicked their successors before leaving office. Thus, the initial promise of democratic accountability and improved living conditions under newly independent African governments proved to be a mirage for many citizens, except for a few self-enriching and corrupt power-holders.

the causes of RECENT coups

Today, while the West continues to fetishise democracy, few of democracy’s promised benefits – good governance, political accountability, the rule of law, the protection of fundamental human rights and civil liberties, the conduct of free and fair elections, constitutionalism, and improved socio-economic conditions – have yet translated into real and tangible dividends for the ordinary citizens of Africa. What we see amongst the causes of recent coups is no longer the constraining power politics of Cold War blocs but a continuity with some of the carryovers of the causes of the first wave of coups. Elections continue to be held, yet they are frequently either fraught with irregularities or rigged to favour the ruling elites. Sometimes, power changes hands; at other times, it does not. Nepotism, corruption, and the personalisation of power continue to plague the governance of some of these republics. The governance space continues to be hijacked by certain ‘imperial’ presidents obsessed with creating dynasties and amending constitutions at will to stave off demands for democratic political change. Ruling elites continue to enrich themselves, their families, and close allies, while citizens wallow in poverty, insecurity, mass youth unemployment and are stripped of their rights to democratic expression.

How are these claims substantiated? In Mali’s August 2020 coup, the junta rode to power on antigovernment protests, accusing President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita’s government of corruption, worsening security, and flawed parliamentary elections. In April 2021, Chad’s president, Idriss Deby, who died on the battlefield, had ruled for three decades in defiance of calls for democratic change. In what smacks of creating a dynasty, his son took over the reins of government without submitting to the electoral process – a breach of the constitution. In Guinea’s September 2021 coup, the military ousted President Alpha Condé, who had illegally amended the constitution a year earlier to overturn restrictions that would have prevented him from running for a third term. Indeed, in the latest of these coups, in Gabon in August 2023, President Ali Bongo Ondimba, whose family had ruled the oil-rich country for nearly 56 years and enriched themselves substantially, was ousted from office. his calls typify the self-absorption and remorselessness that is sadly a manifest trait of many dictators, both past and present, who, in the face of their heinous tyranny, still express a quakeproof conviction of their own ‘innocence’ In a widely circulated video, Ondimba, withering under house arrest, called upon his international friends to “make noise” to galvanise interventions for his release from ‘unmerited’ detention. But his calls typify the self-absorption and remorselessness that is sadly a manifest trait of many dictators, both past and present, who, in the face of their heinous tyranny, still express a quakeproof conviction of their own ‘innocence’.

A new development, often cited among the causes of recent coups, is the menace of jihadist insurgency that has afflicted parts of the region, notably Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. Sadly, these three countries have also been ranked as some of the poorest and most ill-governed countries in the region. A new development, often cited among the causes of recent coups, is the menace of jihadist insurgency Among their myriad grievances, the recent juntas with their supporting masses in all three countries pointed to the unaddressed insecurities from jihadist insurgents loosely affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. The fact that long-standing afflictions in these countries have been exacerbated by this emerging new threat should underscore the depth of citizens’ dissatisfaction with their government’s incompetence in cracking down on this terror.

Some observers have explained the recent coups as a desperate last resort for ending repressive regimes that offer no hope for democratic succession or better living conditions for their impoverished citizens. Proponents of this viewpoint ignore the sometimes irreversible chain of societal upheavals, as well as the possibility for causing long-term political instability, which could have long-term ramifications for a country’s future. This recalls an episode in the French Revolution: when King Louis XVI was informed of the fall of the Bastille by the duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, he exclaimed, “Why, this is a revolt.” “No, Sire”, replied the duke. “It is a revolution.” Africans do not seem to want a revolution; neither is the recent wave of rising coups due to a loss of faith in democracy. Africans do not seem to want a revolution; neither is the recent wave of rising coups due to a loss of faith in democracy. If anything, Africans desire a ‘revolution’ in the drive towards participatory democracy and accountable governance.

Do the recent coups signify a retreat from democracy?

Perhaps the most fundamental question is: “Do the recent coups signify a retreat from democracy?” “Not quite so in Africa,” says Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi, the executive director and cofounder of an independent research network, Afrobarometer, that conducts public surveys on attitudes to democracy, governance, the economy, and society. His findings from an Afrobarometer survey in 34 countries in all regions of the continent between 2016 and 2018 revealed that more than two-thirds (68%) of Africans prefer democratic rule despite their frustrations with the governance of their leaders. Also, 63% of respondents expressed support for multiparty competition, 75% preferred high-quality elections, and 75% supported presidential term limits. He concludes: “Indeed, the proportion of Africans who think it’s more important to have an accountable government than an efficient one increased between 2015 and 2018, from 53% to 62%”, proving that there is still a great demand for democratic governance in Africa. But why has this legitimate demand remained unmet to such a degree?

The answers are legion, but one stands out. The wanton “truncations of constitutional governance” by the military, as one African president has termed it, have arguably contributed to stunting the growth of a robust governance culture over the longue durée of the continent’s 60 years of independence. Many of the continent’s democratic institutions are still weak, restricted by the absence of solid governance cultures. The various arms of the state – the executive, the judiciary, the legislature – and the press in many countries are ineffective and weak, stripped of the independence required to function fully and effectively to fulfil their democratic mandates. a culture of breeding ‘strong men’ and ‘imperial’ presidents has become consolidated, obstructing the development of the culture of good governance and meaningful ownership and use of resources. In their place, a culture of breeding ‘strong men’ and ‘imperial’ presidents has become consolidated, obstructing the development of the culture of good governance and meaningful ownership and use of resources.

The recent coups have attracted a mix of condemnations and sanctions from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the United States, the European Union and various world leaders, underscoring the relevance of these bodies and leaders as watchdogs of democracy. But the watchdogs that are located on the African continent have often been accused of double standards. For instance, after the recent coups, the African Union (AU) suspended Mali, Guinea and Sudan, but not Chad, adding to growing public mistrust over the AU’s effectiveness as a credible and independent watchdog in the region. Further, in September 2021, the Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara, who had illegally changed his country’s constitution months earlier to run for a third term in office, brazenly joined forces with the then president of ECOWAS Nana Akufo-Addo on a one-day visit to Conakry to petition coup leader Mamady Doumbouya for Condé’s release and the restoration of constitutional rule in the country. Indeed, in the eyes of many, the legitimacy of their mission was undercut by the paradox of an ‘undemocratically’ elected Ouatarra assuming the role of a spokesperson for democracy. Such overtures have contributed to the waning image of these regional bodies, often slammed as caucuses of dictators. There are calls for cultivating the culture of cracking the whips of accountability – sanctions and suspensions – fairly and without discrimination There is thus a need for a more proactive and independent African Union and ECOWAS as they continue to act as watchdogs in the region’s affairs. There are calls for cultivating the culture of cracking the whips of accountability – sanctions and suspensions – fairly and without discrimination.

Postcolonial Africa has come a long way in its search for stable and accountable governance. Its path has been rocky, yet any assessment of its failings must view these violent upheavals as salutary, part and parcel of democracy. Africa’s susceptibility to violent political ruptures must not be seen as exceptional in its young history of democratisation. The coups that have rocked the continent in the last 60 years must be seen as a part of its birth pangs – the contractions and dilations of the continent’s prolonged labour inside the delivery room of governance. The continent’s democratic strides, however slow and flailing, are, rightly speaking, a work in progress. After all, what is democracy today in the West if not the product of centuries of effort, punctuated by violent interregnums, especially during its nascent stages?

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

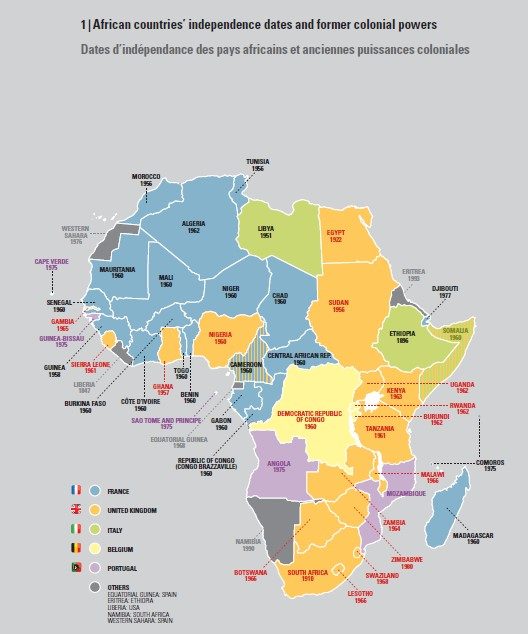

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

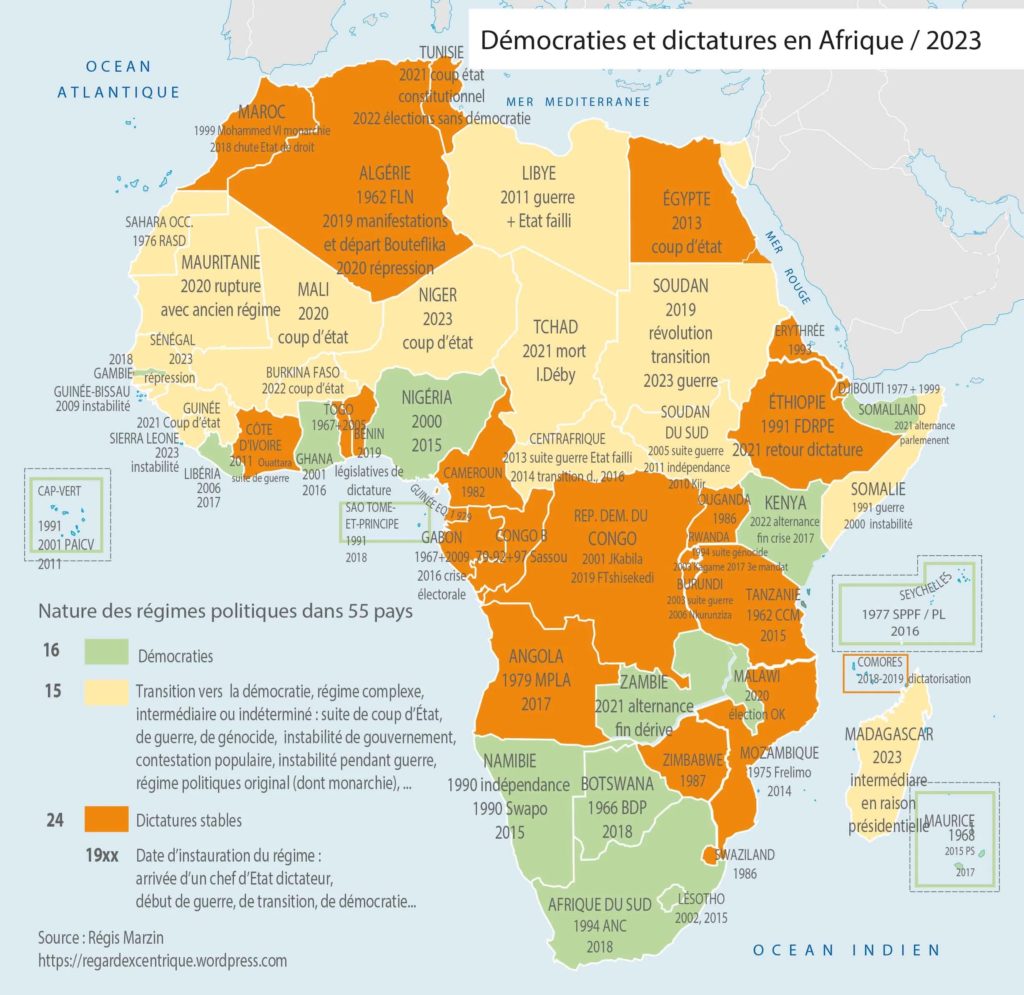

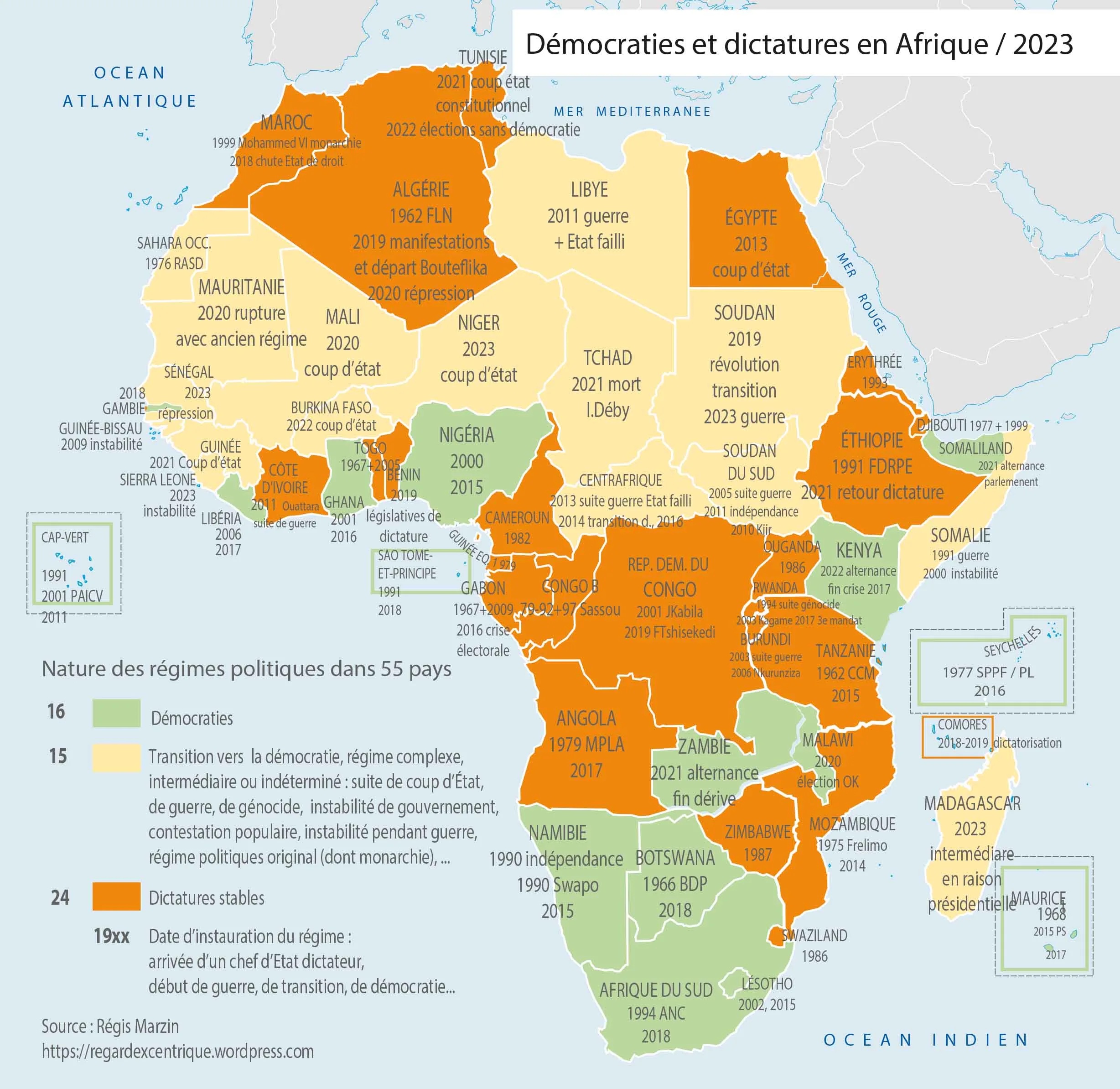

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.