In from the Periphery: How Africa Can Contribute to the Making of a Pluriversal World

A single Western-Eurocentric view of state formation and international relations risks minimising Africa’s role in shaping the international system. It is only by acknowledging other, potentially different, trajectories towards statehood that it becomes possible to move beyond a static “centre vs periphery” worldview.

The growing currency of the “Africa rising” discourse over the last two decades is accompanied by a debate on the place of Africa in international relations as well as how the continent contributes to the making of a world of multiples. The narrative first appeared following what was termed at the beginning of the 21st century by Alice Amsden the “rise of the rest” – i.e., the achievement by certain developing states of high levels of economic growth and productivity.

However, the continued presence of disparities in the distribution of wealth and resources across the globe tends to promote the marginalisation of Africa in a globalised world. In that context, it is important to underline the diversity of socio-economic growth taking place in the region. Besides, demographic projections suggest that by 2050, the sub-Saharan part of the continent will count more than 1.3 billion working-age people. Consequently, it is necessary to take seriously ongoing trends in the region, which is often portrayed without nuance as a blind spot of the world order.

The debate on the role of Africa in global affairs is complex and should be engaged in a multi-layered perspective, as should the analysis of Africa in the discipline of International Relations (IR). The prevailing tension between how experiences from the region inform IR scholarship on the one hand, and the status granted to African agents as second league players in world affairs, on the other, questions the issue of status and hierarchies. A meta-reading of the international system does not capture the contributions of the diverse players and spaces from Africa to the fabric of a pluriversal world. A critical issue at stake is the unequal recognition of epistemes, institutional and social innovations offered by the multiple agents shaping Africa.It is important to underline the diversity of socio-economic growth taking place in the region

If we look only at the European experience of state-building, well described by Charles Tilly as a process mainly structured around war and taxation, how can we make sense of other trajectories – particularly African – characterised by the aggregation of intertwined experiences involving transnational identity communities? For example, how do we value political institutions which pre-existed in the former Empire of Ghana before the British coloniser conquered this West African nation? Does the continued differentiation related to African socio-political peculiarities simply serve to perpetuate double standards and asymmetries in knowledge production?

The prevailing context of epistemic hierarchies restrains the prolific contributions that Africa and more broadly the Global South can offer to the IR discipline, not just as a place to collect raw materials, but also as a space where innovative contributions can emerge. A critical move towards better capturing ongoing trends on a global scale is to provide equal recognition to Africa’s experiences as relevant contributions to the making of our pluriversal world. This necessitates broadening our schemes for thinking and apprehending how the global arena works. For instance, how do we better take into consideration relational ontologies promoted by the Pan-African doctrine as the foundation of the continent’s engagement in world affairs? How do we better take into consideration relational ontologies promoted by the Pan-African doctrine as the foundation of the continent’s engagement in world affairs? As advocated by Kwame Nkrumah and his Pan-African peers in 1960s, taking into consideration social morphologies linked to particular spaces is an important way to adopt a balanced perspective that encompasses multiple worldviews. Doing so prevents a hierarchical understanding of the international system, beyond a static and binary centre-periphery configuration.

A close look at African states’ engagement in world affairs through the African Union sheds light on how playing the regional game becomes a privileged strategy for promoting and asserting Africa’s views on global issues. In 2018, the African Union, based on the Pan-African doctrine, recognised the African diaspora as the sixth subregion, which is a unique institutional innovation for promoting African regionalism. In the same vein, the 9th Pan-African Congress, to be held in Lomé in late October 2024, will focus on the theme “Renewal of Pan-Africanism and Africa’s Role in the Reform of Multilateral Institutions: Mobilising Resources and Reinventing Ourselves for Action”.

The decision in September 2023 to make the African Union a permanent member of the G20 is a paradigmatic example of the growing recognition of Africa as a regional player. Promoting the Pan-African doctrine of “Try Africa first” is grounded in shared experiences and is driven by a continual search for a common denominator. It sheds a particular light on the vivacity of the African regionalism, and consequently gives voice to a certain global vision of our common future, that we should listen to more. Ultimately, it is a call to better value the multifaceted configurations and views Africa offers in the making of a pluriversal and inclusive world.

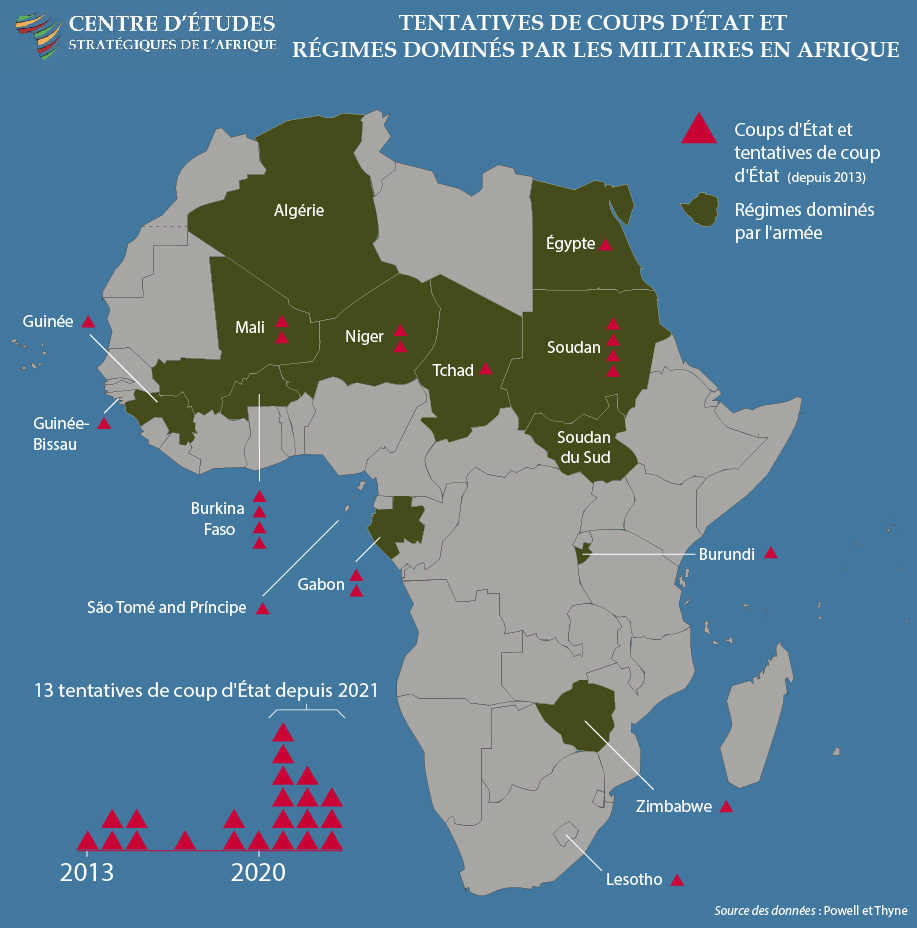

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

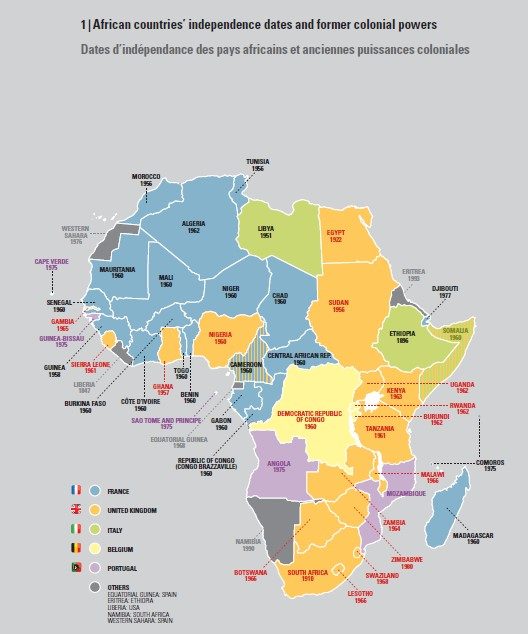

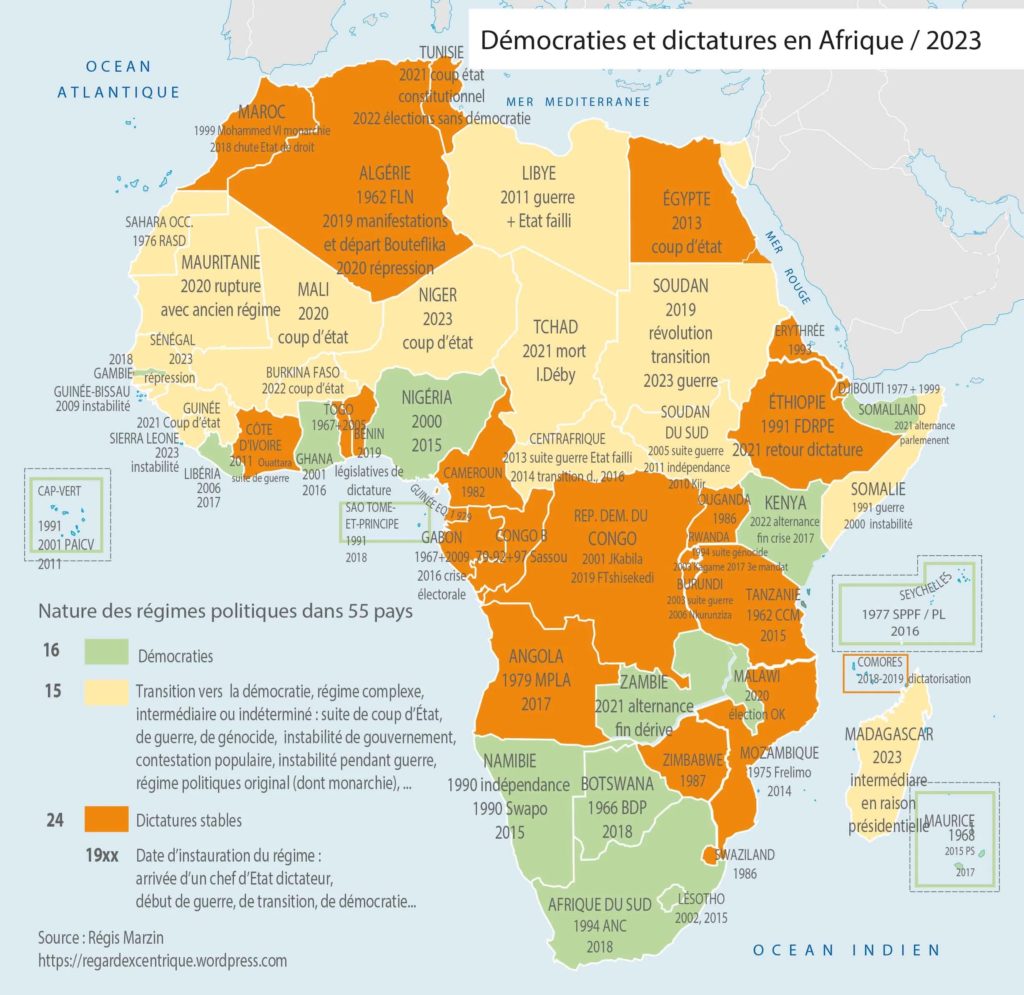

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

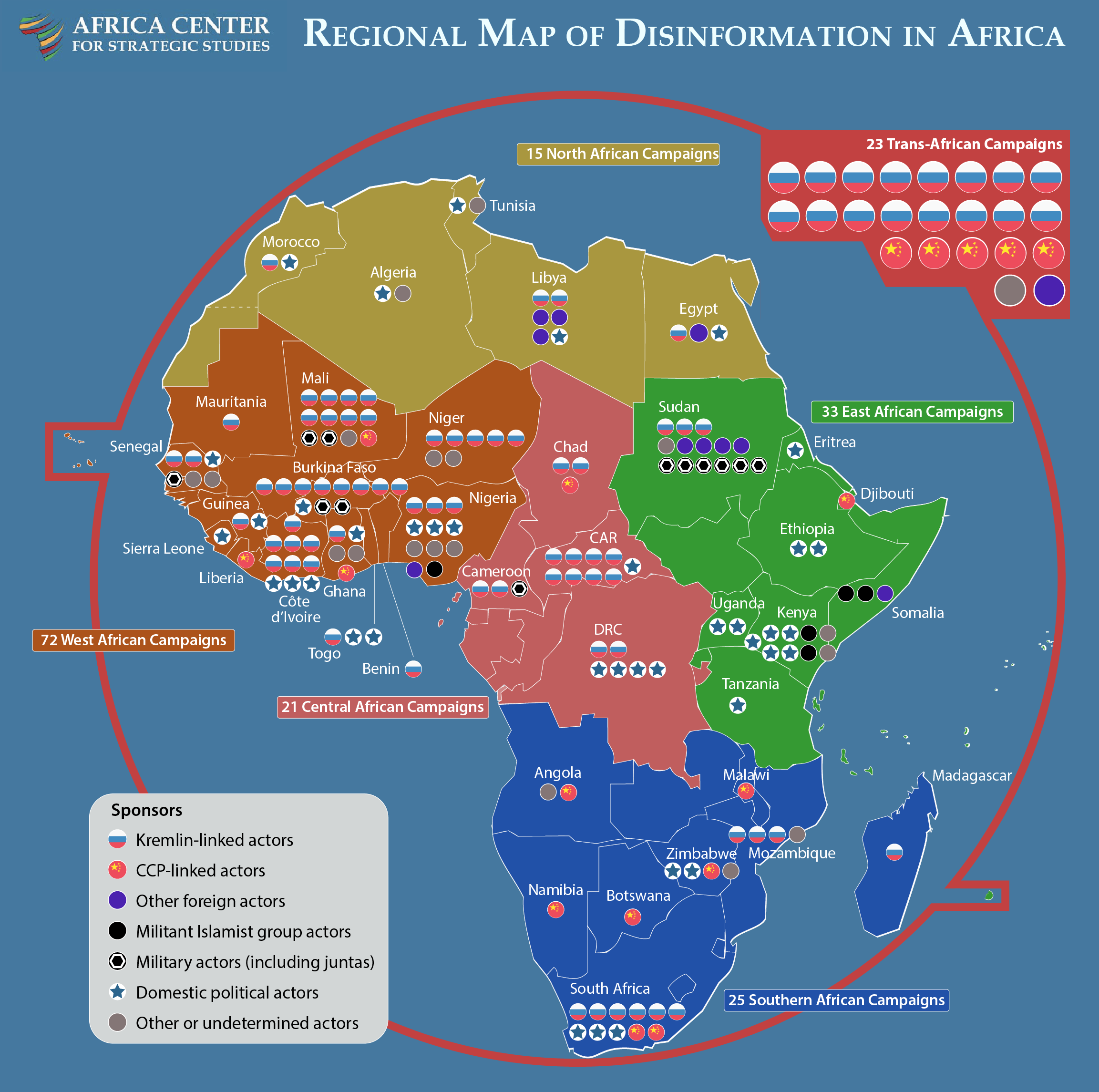

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

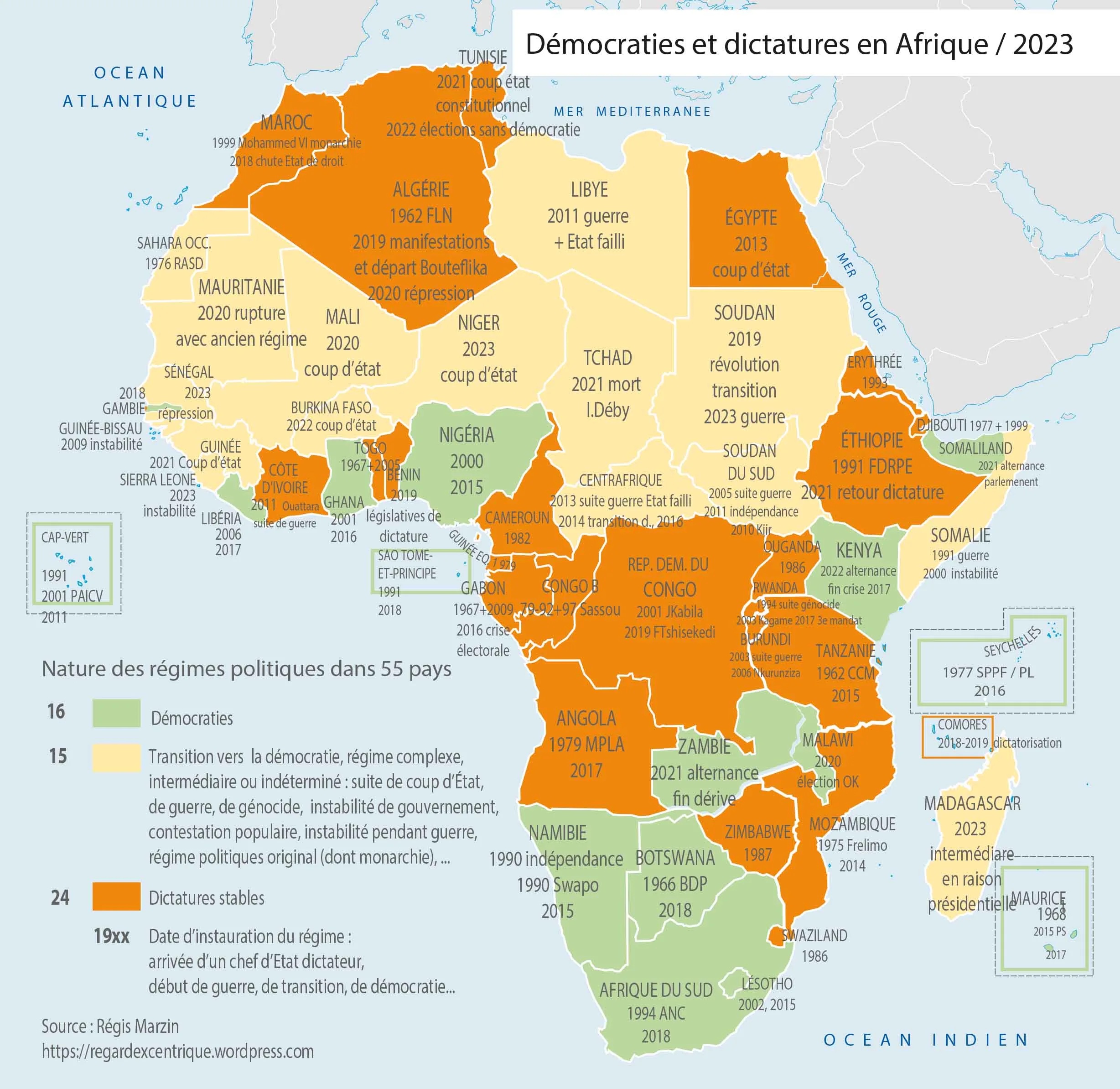

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.