Towards Greater Visibility of African Women in Politics

Although they have generally had less visibility than their male counterparts, women have long played a key role in African national liberation movements, including, more recently, in South Sudan. As more African women obtain higher-ranking political positions, women are now also becoming an increasingly important force in the political arena.

In the documentary No Simple Way Home (Akuol de Mabior, 2022), the fourth Vice President of South Sudan, Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior, says to the film’s director, “What you are doing here is politics … You are registering history.”

This statement is significant because the documentary highlights the contributions of a female politician to the liberation struggle of South Sudan and the country’s peace-building process. In post-conflict periods in Africa, men often dominate what Katherine A. Roberts describes as the “war of symbols”. Men dominate the war of symbols or the struggle over meaning production that often characterises nation-building processes because they occupy most decision-making positions in sites of meaning production, such as state-owned media. Women are usually relegated to supporting actors and recipients of state policies. This impacts women’s claims to political legitimacy because political leaders frequently justify their political authority by emphasising their roles in liberating their nations from, for example, colonialism or dictators. It is, therefore, critical to make the contributions to nation-building of women politicians and political activists visible in national narratives.

Some women have attained higher-ranking political positions that attract media attention and give them more significance in national and international politics There has been a significant shift towards greater visibility of African women in politics in recent years. This increased visibility has partly been because some women have attained higher-ranking political positions that attract media attention and give them more significance in national and international politics. These women include Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, who became the first elected female head of state in Africa in 2006; Samia Suluhu Hassan, who became the president of Tanzania in 2021; Joyce Hilda Banda, who served as president of Malawi from April 2012 to May 2014; and Joice Mujuru, who served as vice president of Zimbabwe from 2004 to 2014.

The visibility of African women in politics is also enhanced by the representations in films of their experiences and significant contributions to liberation wars, peace-building and post-conflict nation-building processes. Examples of such films include Pray the Devil Back to Hell (Gini Reticker, 2008), which focuses on a group of Liberian women who came together to end the war and bring peace to their country; Nzinga, Queen of Angola (Sérgio Graciano, 2013), which focuses on Queen Nzinga, the 17th-century queen of the Ndongo and Matamba Kingdoms, located in present-day Angola, who led her people in a fight against Portuguese colonial forces; Winnie (Pascale Lamche, 2017), which focuses on Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and her contribution to the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa; and No Simple Way Home, which underscores Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior’s motivation for political action and her perception of her role in South Sudan’s politics. These films highlight the realities, challenges and roles of African women politicians and political activists in claiming women’s political legitimacy and promoting democracy.

In No Simple Way Home, Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior is referred to as Mother of the Nation. She joined the Sudan People’s Liberation Army and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) during what is often referred to as the Second Sudanese Civil War, which lasted more than two decades from 1983 to 2005. In the documentary, she states that she wanted to help her husband, John Garang de Mabior, who founded the SPLM in 1983. But, beyond that, she was convinced that she had to contribute to liberating the people of the South (of Sudan) from an oppressive regime. She continued her fight after the death of her husband in 2005. After South Sudan achieved independence in 2011, she continued to fight for democracy. She says, “Because I was part of the struggle, I wanted to be also part of the nation-building” as a citizen of South Sudan. In claiming her citizenship, she also asserts her political legitimacy. Like many women politicians in Africa, Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior is keenly aware of the significance of her visibility, her strong voice in South Sudan politics, and the responsibility that comes with that. Her fight for democracy led her to be forced into exile in 2013 after criticising the SPLM leadership, which she says is doing worse to the people of South Sudan than what “the enemy” did. She loudly declares, “I will not keep quiet.” She demonstrates a strong sense of responsibility because she does not make excuses for herself, often referring to the leadership she criticises as “we” and “us”. And by using “we” and “us”, she also places herself at the centre of the country’s political narrative.

Like many women politicians in Africa, Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior is keenly aware of the significance of her visibility, her strong voice in South Sudan politics, and the responsibility that comes with that: “I am a role model to the young ladies.” She sees it as her responsibility to show young women that they, too, can claim their political legitimacy and be leaders. She echoes the voices of many African women politicians who point out that women are often pushed towards underfunded departments, such as those dealing with women’s affairs, gender and social welfare. But she believes these departments are essential too, and a concern for people’s welfare can enhance a politician’s popularity and visibility.

Through meaningful representations of their presence and voices in the media, it is becoming increasingly clear that African women are agents in nation-building rather than mere recipients of state policies. Their increasing visibility in politics could potentially contribute to democracy by enhancing the plurality of political voices.

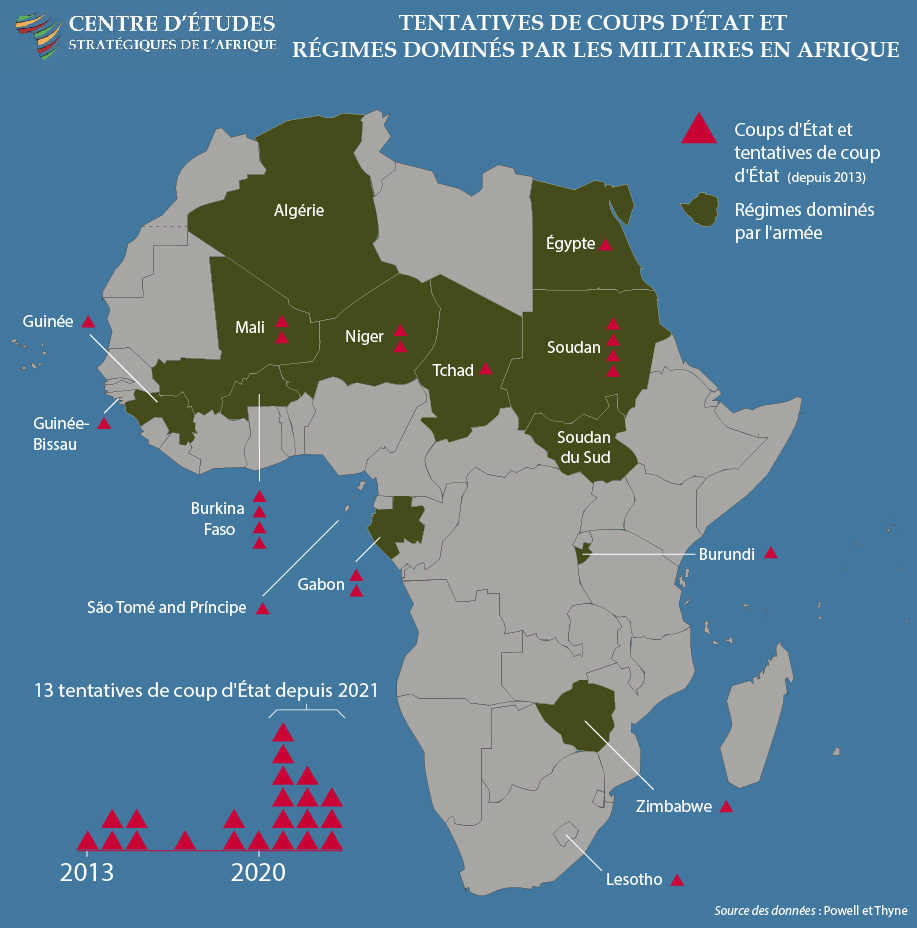

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

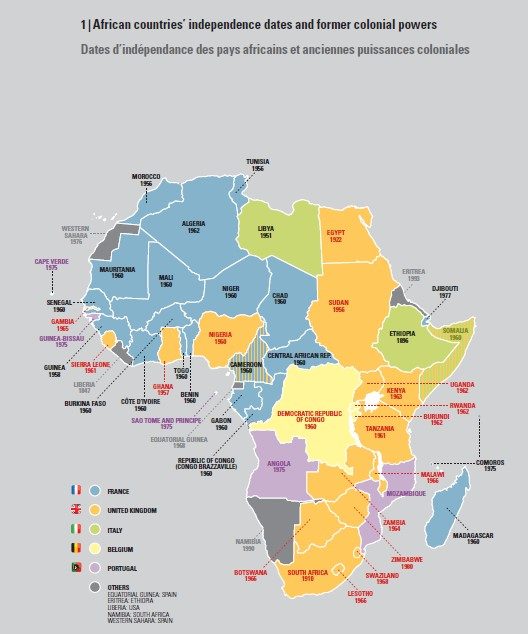

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

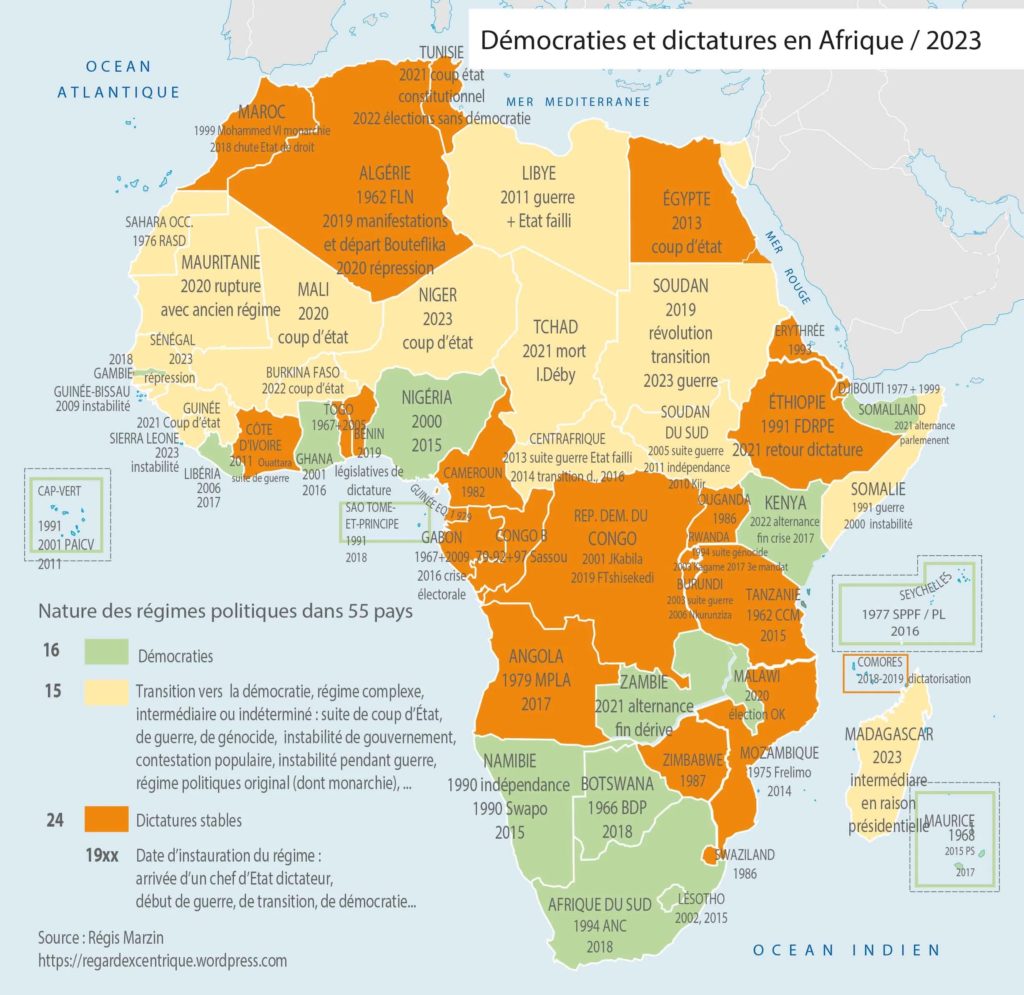

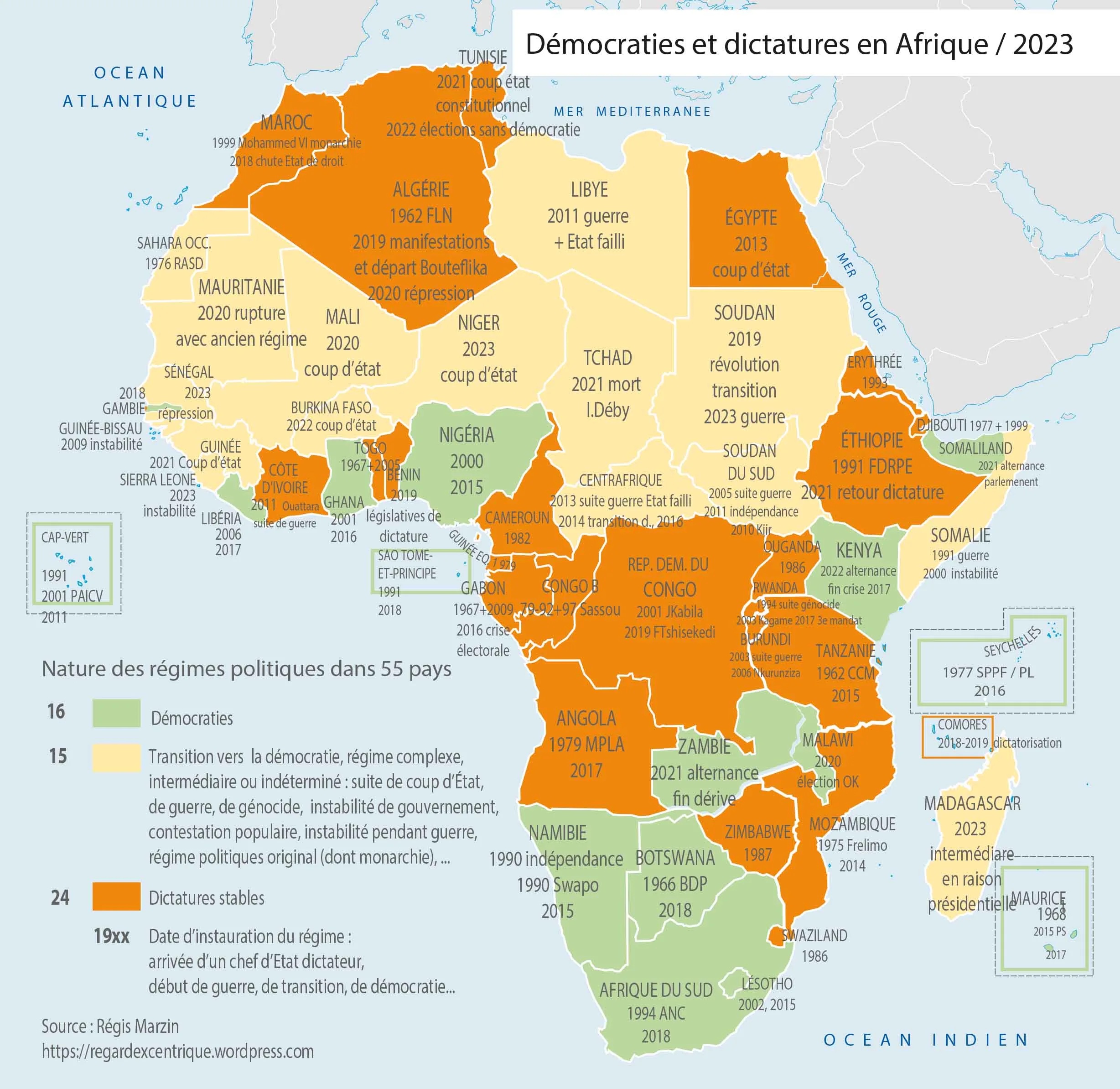

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.