Decolonisation and Humanitarianism

Humanitarianism in its transnational and international forms is generally studied separately from domestic humanitarian activities. Moreover, humanitarian interventions – i.e., enforcement actions carried out since the beginning of the 19th century by governments to end violence and atrocities against foreign civilian populations – are often studied separately from humanitarian actions carried out by individuals or organisations. Yet humanitarian practice mostly originates in a specific place and is not necessarily conceived of as transnational or global; in the past and today, it tends to be local and, I would add, provincial. Aid for the poor and sick, for example, was not conceived as a transnational activity. It has at times been motivated by ancient religious principles; it has at times been the work of (private or semi-private) public service institutions for the benefit a local community to which the donors also belonged; or, since the 19th century, it has also at times been the result of a targeted action by several states. For a long time, humanitarians were also nationalists – the contrary would have been surprising – and still today, the worldview of the vast majority of humanitarians is based on the nation state. As such, transnational humanitarian action has been neither apolitical, nor universal nor systematic. Aid for injured soldiers or prisoners of war, for example, was for a long time reserved for soldiers belonging to “civilisations” that shared the same standards as their benefactors.

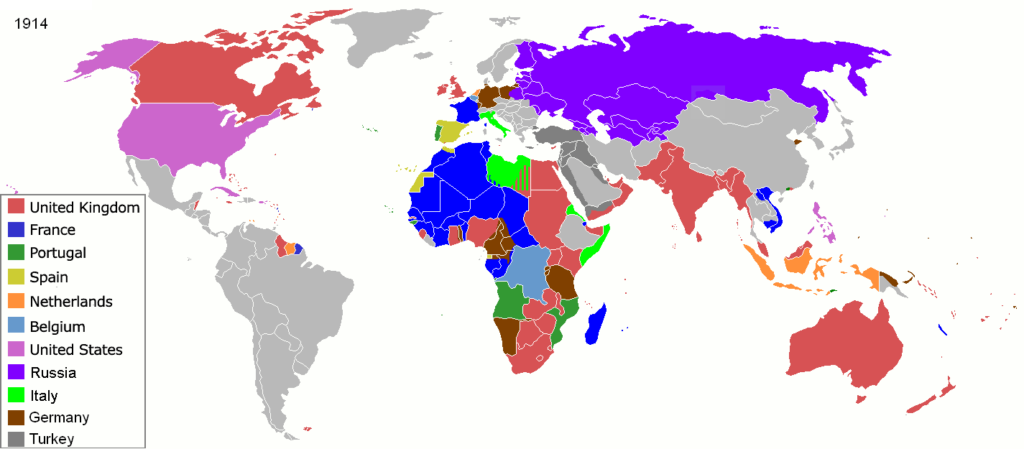

Humanitarianism’s transnational “leap” was thus not systematic, nor indeed a solely Western prerogative. Other cultures, civilisations and religions, in particular Islam, have ancient and sophisticated practices of charity, voluntarism and mutual aid. In its Ottoman version, a trans-imperial humanitarianism existed during the period when European colonial expansionism was at its peak. Thinking of humanitarianism as a Western invention is incorrect, as is excluding a priori the possibility of a non-Western humanitarianism – or indeed a non-Western colonialism.

In its transnational version – seeking to help or relieve the suffering of foreigners in need – Western humanitarianism has accompanied European expansion since the Conquista and the proslavery and abolitionist movements, well before colonialism’s “golden age”. Moreover, in continental colonial expansions such as in North America, religious and philanthropic organisations were among the heralds of the conquest, distributing charity and helping establish the state.

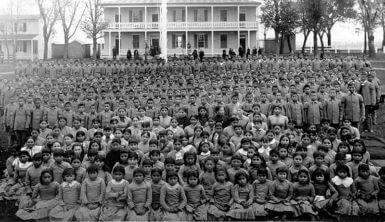

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania, c. 1900.

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania, c. 1900.Consider, for example, the education of indigenous populations (including at boarding schools, about which the media has reported at length this year), urban development, public health and aid for orphans and the poor – and for the “deserving poor” in particular. The same religious and philanthropic actors were to be found among the protagonists of the “liberation” (sic) and civilisation of Hawaii, Cuba, Haiti or the Philippines, as well as in the segregation of African Americans in the South (and in the North) of the United States. As such, considering all forms of colonialism helps us consider all forms of humanitarianism.

Seen across this longer timeframe, a colonial and racist side to humanitarianism is evident. Humanitarians ahead of their time, children of Europe’s cultivated élites – whether missionaries, philanthropists or agents of the state – were imbued with moral and religious (Christian) principles onto which were grafted the racist and eugenic theories of the 19th century. The beneficiaries of charitable acts knew that the humanitarians (who did not yet bear the name) came together with, not against, the colonisers. The purported rescue was not in response to an explicit or implicit request from its beneficiaries; moreover, any rescue would have been superfluous had the colonial enterprise itself not taken place, thereby confirming the notion of humanitarianism as a by-product of colonisation. Being surprised about this would be as hypocritical as it is pointless.Thinking of humanitarianism as a Western invention is incorrect, as is excluding a priori the possibility of a non-Western humanitarianism – or indeed a non-Western colonialism.

In light of its long history, humanitarianism in the age of decolonisation should therefore not be studied in isolation. Decolonisation did not bring with it a fundamental change in the paradigm of international humanitarianism. Humanitarian organisations have in the past adapted to contexts where the international order and national sovereignties were in flux. Thus, during the Cold War, Western international humanitarianism could only operate in the gaps left – at the cost of bitter and complicated negotiations – by the two great powers. This is why Biafra was a theatre of humanitarian hyperactivity at the end of the 1960s, leading to the creation of Médecins sans Frontières, whereas international humanitarian action remained very modest in Brazil, Chili, Argentina or Czechoslovakia. The ephemeral period of unilateralism after the fall of the Berlin Wall opened spaces that humanitarians seized, as they had already done between 1918 and 1927. The humanitarian space has always been characterised by its variable geometry, a fact that somewhat relativises the narratives about its current narrowing. And whether, and to what extent, Western humanitarianism has undertaken its own decolonisation is an issue that still requires more systematic exploration.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.