Decolonisation: Too Simple a Term for a Complicated History

Decolonisation is a difficult historical object to grasp. Its ideological connotations encourage us to understand the term in evolutionary and normative terms, with the nation state and nationalism seen as natural points of reference through their association with anticolonialism. Anticolonialism, however, is not necessarily nationalist and does not necessarily result in the independence of a nation state. Numerous political leaders in French-speaking West Africa aspired to postcolonisation in a rejuvenated republican political framework that was federal or even imperial. The creation of Pakistan was not a foregone conclusion either and, what’s more, Pakistan broke into two.

Conversely, colonial nationalism has spawned declarations of independence, as in Latin America or South Rhodesia, or dominions, as in Canada, Australia or South Africa, without bringing decolonisation for their “indigenous” peoples. There are also situations where decolonisation has taken place in the absence of a dominant nationalist party – as in Belgian Congo or Angola; in a context where the main nationalist party has been repressed – as in Cameroon; or in the crucible of a fratricidal struggle in the context of wars of national liberation – as in Angola, Zimbabwe, Algeria, Eritrea and Indochina.

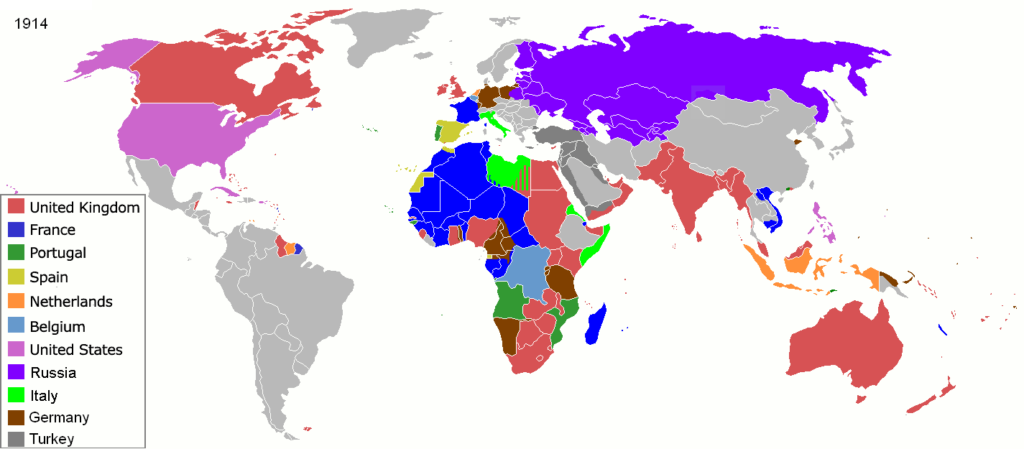

Moreover, colonialism has not been the sole prerogative of Western states. The Victorian Raj extended colonial-style Indian domination to Malaysia and Burma, to the Gulf and to West Africa, subsequently jeopardising the independence of the successor states to the British Empire. Historians describe this as a “secondary empire”; Marxist theorists call it “sub-imperialism”. Viet Nam colonised Cambodia (1806–1846); Japan colonised Taiwan (1895–1945), Korea (1905–1945) and Manchuria (1931–1945). Indonesia annexed West Papua in 1962. The decolonisation of Xinjiang today is not on the Chinese agenda.

Europeans, too, have lived under the colonial yoke: in Ireland, Cyprus or in the Dodecanese. Already in the Middle Ages, Venice (throughout the Eastern Mediterranean) and Aragon (in Sicily) were the prototypes of colonialism in the modern sense of the term. Today, Germans in the Ostländer refer to their Kohlonisation – no doubt with some excess.

Musée McCord, Québec.

Musée McCord, Québec.The generic term “decolonisation” thus fails to take account of this broad range of scenarios, to the point that it’s not clear that it still makes sense to use the term. What about the independence of the former Soviet Republics in Central Asia, for example?

In contrast, we now understand better that decolonisation does not entail a radical discontinuity either in the former colonies or in the former metropolises. Postcolonial Studies is correct to remind us of this, but it remains caught in a binary vision of colonisation in the form of an opposition between colonisers and colonised, minimising the appropriation of the Western graft by the latter and the ambivalence that followed. It finds itself trapped in a kind of tropical Calvinism that treats colonisation as predestined, overdetermining the subsequent history of the colony and its metropolis alike.

Another debate, influenced by the Indianist school of Subaltern Studies, concerns the reproduction of colonial hegemonies after decolonisation within African or Asian societies, for which nationalism is said to be the vector. It was this that Frantz Fanon was afraid of when he asked the “wretched of the earth” “not to imitate Europe”, to renounce “nauseating mimicry” and to reject the creation of “a third Europe” in the likeness of the United States. Intellectually, Frantz Fanon was correct, but politically, he was mistaken. Contemporary violence is predicated on the idea of challenging the domination that still today proceeds from the appropriation by colonised societies – and their élites in particular – of the Western nation-state, its épistémè, its relationship to capitalism. Thus jihadism in the Sahel.Postcolonial Studies finds itself trapped in a kind of tropical Calvinism that treats colonisation as predestined, overdetermining the subsequent history of the colony and its metropolis alike.

In its agrarian dimension, however, this jihadism also reminds us not to separate the paradoxical continuity of decolonisation from the continuity that colonisation itself often represented with regard to previous political societies. In particular where European occupation enabled the dominant social classes to extend their control by virtue of the state’s resources and a modern economy, as in Morocco, in Northern Nigeria or in the Punjab. But also when lower social classes seized the colonial moment to launch a true revolution against the previously dominant groups, as in Zanzibar in 1964. Evidently, it has been scenarios in between these two extremes that have generally prevailed.

The old division into precolonial, colonial and postcolonial eras does not stand up to scrutiny. The advent of decolonisation must be read in the light of these continuities woven from discontinuities. Bergson would have referred to the “compenetration” of durations, within which the traumatic memory of slavery and colonial occupation is a “memory of the present”, a “false recognition” about which Postcolonial Studies has little to say. For all that, the intensity of the event of decolonisation should not be diminished by relativising its importance. It has given substance to an assertion of dignity and a thirst for freedom that will never be extinguished, despite the sometimes shocking or bewildering forms they may take today and the disillusion that followed the euphoria of independence.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.