Decolonising International Politics

The othering of critical perspectives on global affairs is the Achille’s heel of contemporary academic studies of international politics.

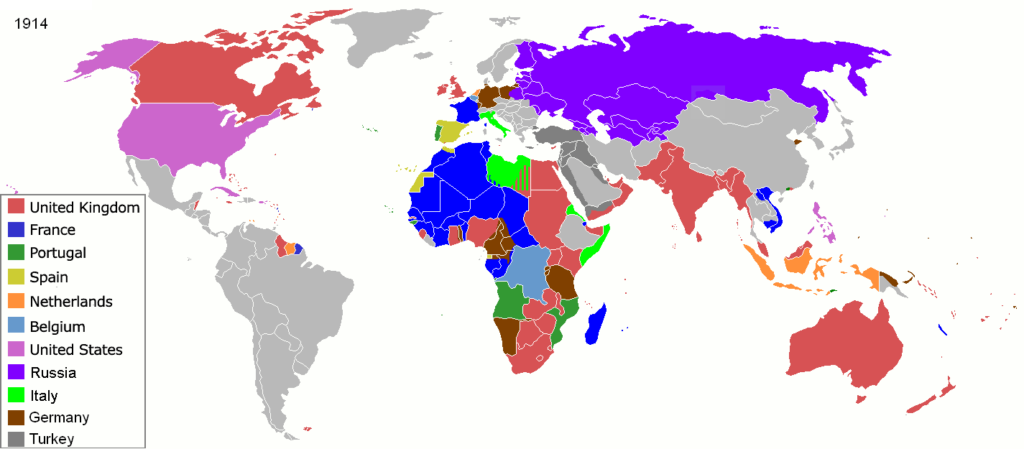

The modern-day academic study of international politics was born out of a political concern to make sense of the set of issues besetting western colonial and imperial states. This genealogy is crucial in understanding the evolution throughout the twentieth century of many historical and social sciences fields concerned with the study of international affairs. The incipient concerns were centrally those of colonial administration and imperial rule.

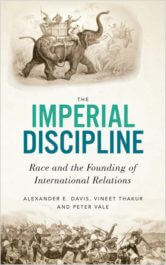

International law has long been conceived as a project of codification of rules followed by imperial powers as they interacted with one another[1] – and the same could be said of conventional diplomatic history. Anthropology and sociology have entertained a deep connection with colonial administration from their early days onward, especially in the interwar period.[2] Today, this founding and formative orientation built around the requisites of regulation and command still characterises some scholarship in international relations (IR) and political science; the colonial (or segregation in the case of the United States) context accounts, additionally, for the discipline’s active avoidance of racial issues. As it emerged and acquired scholarly pedigree in Europe and the United States from the mid-1910s on, the discipline of “IR”, for instance, continuously and exponentially shared this Belle Époque arborescence, which problematically has not been widely recognised as such – thus minimising and at times invisibilising the implications of a specific regional historical context of state-led control, domination and dispossession.

Today, international politics remains largely taught and conceived by a variety of disciplines as the province of the ins and outs of power-, sovereignty- and capital-driven interaction primarily amongst states and state-derivative organisations and structures – thus intellectually and globally curbing the notion’s nomothetic realm. To wit, when not wholly ignored, criticism of the imperial core of each discipline has tended to be associated with the angling of postcolonial studies, or located in peripheral sectors of each of these fields, relegated as it were to “alternative perspectives” status and in effect delegitimised in relation to the central canon of a handful “core” theories or canonical texts presented as universal, directive and self-standing. To add to injury, founding thinkers of any given field, or earlier philosophers associated with its tenets, are overwhelmingly if not exclusively Western: Kant, Grotius, Hobbes and Thucydides in the case of IR, or Marx Durkheim and Weber in sociology, more often than, say, Ibn Khaldun – who largely remains unknown to most students of international affairs in Anglo-American as well as European universities.

Such implicit or explicit othering of critical outlooks on international politics is arguably the Achille’s heel of contemporary international affairs. It is the ever-fixed sidelining hue that still largely dominates programmes taught around the world, both in the Western and non-Western worlds. Understandably, this has led many critics of such academic fields to seek to open new niches or to shed light on missed aspects. Decolonising international politics is not, however, merely about “giving voice to” or allowing visibility of “alternative” views – such an approach still partaking of a logic of authorisation. Neither is it about self-reflexivity and reform. Rather, the needed intellectual rupture is primarily one of the very method and ambit, as well as the history presiding over the field.

For far too long, the very categories of “learning global affairs” have been arranged in a way that positions Eurocentrism – even when that worldview has been largely exposed by a variety of perspectives – as the formative pillar of a deliberate production. As Julian Saurin remarked, “the assertion of Western supremacism and its corresponding discounting or silencing of ‘the rest’ is not primarily an intellectual or, for that matter, an epistemological trick, conspiracy or malign intent but rather ”.Decolonising the study of international politics is not about “giving voice to”; rather, the needed intellectual rupture is essentially one of method and ambit

It is precisely this structured production that is in need of discontinuation – not merely the reexamining of its construction – in light of its reproductive self-legitimation and creative reinventions. Today impeding a clear-eyed outlook on the deep history behind global politics, the imperial and colonial DNA of our disciplines has led some of their main representatives to prioritise interpretative outlooks in which students are trained as system designers whose inquisitive gaze is lured away from the why. This is an age-old epistemological trick derivative of the initial bent to avoid the politics – and thus the illegitimacy and violence – of imperialism and colonialism, and their consequential afterlives. As a result, more often than not, the study of international affairs has accompanied rather than questioned international developments.

The hollowing out of the provincialism that has driven this specific understanding of the “march of the world” on the drum tempo of empire and colony (foreign affairs, militarism, “great men”, geopolitics, diplomatic history) explains why today the notion of security remains at the heart of international relations, and why – in spite of their direct lineage to the discipline – race matters are of little concern to most contemporary scholars of international affairs, except for a few notable exceptions.[3] It is the reason for which the phraseology of terrorism came of age since the 1960s, revealingly boxing the emancipation of the decolonised actors. It is why paternalistic talk of “failed”, “collapsed”, “fragile” and “weak” states dominates since the 1990s imparting a dichotomising geography of the world, and a related sense of mission that had been there at the origin. It accounts, finally, for how in the 2000s manifest Eurocentrism could be (re)asserted in international theory, and why ultimately it is so urgent to produce genuinely neutral and universalist analyses of world politics.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.