Decolonising the Global

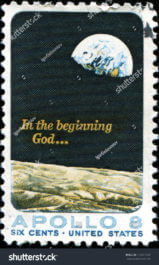

In now decades-old theories of globalisation, numerous scholars have placed weight on the conceptual impact of the first images of our planet seen from the perspective of the moon. The photographs, taken during the Apollo 8 space mission and known collectively as Earthrise, offered a nascent glimpse of the earth as a single sphere.

From a lunar vantage point, hustle-and-bustle megacities appeared as silent clusters of twinkling lights. Oceans seemed like glossy blue fields touching the curved edges of green and brown swaths of land – now visible, now hidden – as clouds formed, hovered and changed shape. This vision of a singular container of human life, unbroken and unbothered by national borders, seemed to give geological credence to a philosophical and political cosmopolitanism. As in the hopeful geo-universalism of Immanuel Kant: “For peace to reign on Earth, humans must evolve into new beings who have learned to see the whole first.” Centuries later, seeing the whole from above became possible in step with terrestrial travel and information technologies that crisscrossed the land, sea and air, fusing the continents, connecting household to household in new forms of remote intimacy. In the words of the media theorist Marshall McLuhan: “The new electronic independence re-creates the world in the image of a global village.”

In each case, from Kant to McLuhan, we hear calls to rethink the relationship between self and other – politically, ethically – through a broadened concept of what constitutes home: the earth itself serving as a shared dwelling place. What is more, the ethics of a global environmentalism grew too from these images of a single earth. For in a dark plot twist, the very technologies that allowed us to connect threatened to destroy the beauty and even the viability of our shared planetary village. Thus, the vocabulary of collective green stewardship emerged to further enrich the centuries-old language of transnational cooperation.

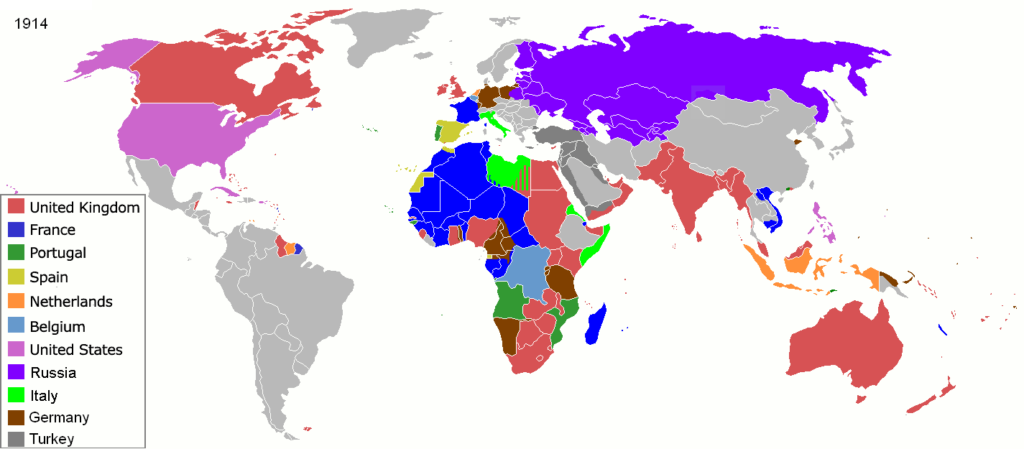

Such calls to think and act in a global key, however, have sometimes side-stepped the extent to which images of the “globe” and the “global” – long before Earthrise – also occupied the fantasies of imperialisms. We might think of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) when the Spanish and Portuguese empires apportioned the known earth into two parts. Or, we could recall the Berlin Conference (1884–1885) when the major European imperial powers surveyed and divided the earth’s still unconquered territories between themselves. In each case, a specific vision of the whole world preceded or justified imperial efforts to subjugate and remake other territories using a uniform template.The very concept of a global society continued both to reflect and in some cases to reinforce inequitable international distributions of power and resources.

Compared to these explicit conquests, it might be tempting to read late twentieth-century references to the unified earth as somehow signifying a break with the world-ordering impulses of formal imperialism. After all, the global village thesis as well as the genre of environmentalism inaugurated with Earth Day (1970) emerged alongside decolonisation – the historical process by which once colonised peoples gained political sovereignty. And yet, as postcolonial studies scholars have long argued, those discourses of cultural, political and ecological unity often carried the same Eurocentric and universalist assumptions that undergirded imperialism to begin with. In other words, the very concept of a global society continued both to reflect and also in some cases to reinforce inequitable international distributions of power and resources. Some scholarly texts, such as Ha-Joon Chang’s provocative Kicking Away the Ladder, have even argued that global climate change objectives created fresh obstacles for developing countries seeking to close the North-South wealth gap.

Rather than taking sides here, what we can gain from thinking with such critical perspectives is a sense of how the globe is not just a place, but has a historical existence as a highly contested and frequently politicised idea. For instance, even the conceptual impact of Earthrise can’t be fully decoupled from the tense geopolitical context of the Cold War or the space race. This leads to another interrogation: if the very concept of the global is covered with now hidden, now explicit fingerprints of political and economic imperialism, can we ever speak of globality in neutral terms? What framework remains for making sense of the increasingly transnational nature of our lives, including the ecological consequences of a capitalist modernity?

As one tentative answer, the renowned postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak has suggested we replace the term global with that of planetarity. Notice, she does not say planetary but rather planet-ar-ity, which mobilises the suffix ity to imply an ongoing condition. Most importantly, the framework of planetarity accounts for what we might call the “facts” of the global condition, without folding them into a hegemonic fantasy of perfect unity. In Death of a Discipline, she states: “I propose the planet to overwrite the globe…. The globe is on our computers. No one lives there. It allows us to think that we can aim to control it.” Here then to decolonise the global in the frame of planetarity is not to arrive at a clear and simple guiding principle for steering the human community to a specific end point. It is an orientation rather than an objective. It is more like a collection of short stories than a novel.If the very concept of the global is covered with now hidden, now explicit fingerprints of political and economic imperialism, can we ever speak of globality in neutral terms?

Of course, this still leaves us with other concerns. In an era of conspicuous climate change, it might seem dangerous to divest intellectually of cohesive narratives at the planetary scale. However, Spivak’s point can be followed to the opposite conclusion: any “natural”, unexamined or overly abstract vision of the earth can end up undermining rather than advancing the nitty-gritty work of environmentalism. Planetarity is a practice of reading and thinking about innumerable webs of interaction that spill across borders, without giving in to reductionist theologies of “one world”. Such silhouettes might be ideologically satisfying, but they rarely help us account for the fuller network effects of our multitudinous words and deeds at any given moment, in any given place.

To conclude, planetarity is also different than a mere affirmation of a positive multiculturalism; it is something closer to labour than to the pomp and circumstance of a concluding ceremony. We (all) occupy the planet, and yet can never speak of that occupancy as a single phenomenon, nor can we describe it with a single voice. So, we are left with the continual efforts of transcribing and translating the constraints and possibilities of so many lifeworlds shaped and yet uncontained by borders. Following Spivak, such is also the nature of the work of resisting all manner of imperialisms old and new, near and far. Perhaps the root principle of planetarity (and so of anti-imperialism) is a form of awe. Awe for that which eludes even the most forceful grasp, including the earth’s fragile splendours.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.