Decolonisation and International Law

After a long period of complicity with colonialism and its agents, international law continues to sustain an unequal distribution of power and resources. Developing countries in particular find themselves subject not only to almost all of the world’s military interventions but also to an investment arbitration regime that is premised on the protection of Western interests.

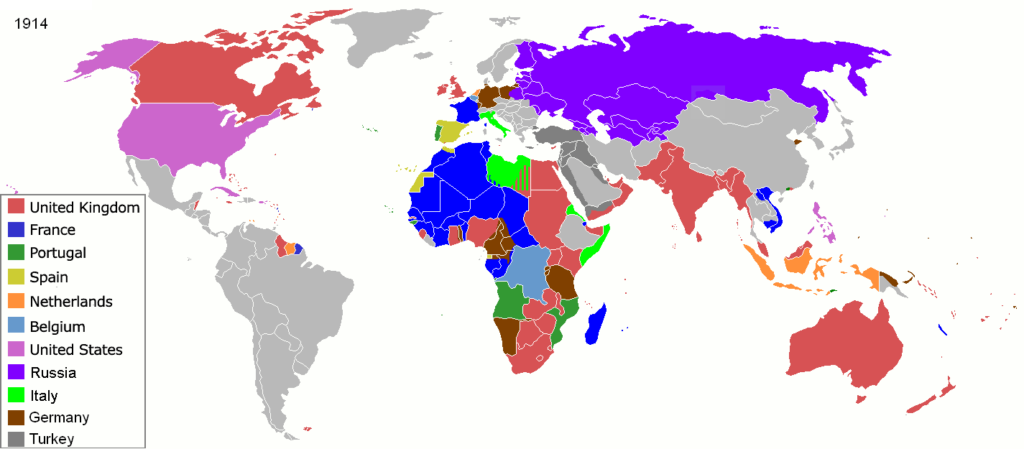

No discussion of international law’s relation with decolonisation would be fair without a reminder of the international legal order’s shameful complicity in colonialism. Historically, international law made colonisation and various dependent international statuses legally possible. It was in its name that numerous non-European human communities were categorised and treated as inferior, “uncivilised” and incapable of self-government. But international law has also facilitated the accession to independence of a significant number of former colonies, largely contributing to delegitimating overt colonisation and enabling colonies to frame their claims in terms of legally recognised rights such as self-determination or the permanent sovereignty over natural resources.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that international law has redeemed itself from its dark colonial past, even if one were to equate decolonisation with the accession of the former colonies to independence. International law is still largely shaped by the “colonial matrix” (Walter Mignolo), sustains unequal distribution of power and resources and has even kept part of its colonialist vocabulary (“terra nullius”, “civilised nations”, etc.). The adjective “international” acts as a powerful camouflage hiding the colonial overtone of international law, casting it as a site of neutrality and universality – a view from “nowhere” that is not associated with any state in particular. Even a cursory glance at the practical operation of international law shows, however, that the international legal order is, among other things, a continuation of colonialism by other means.The international legal order is, among other things, a continuation of colonialism by other means. Despite international law’s supposed neutrality, the developing countries are almost exclusively on the receiving end of “monetary and military interventions” (Anne Orford), international criminal justice exclusively targets developing countries, and the entire edifice of investment arbitration rests on the premise that the legal systems of developing countries do not allow for adequate protection of foreign investments.

Unmasking such colonial legacies is key to any genuine project of decolonisation. It is necessary, however, to go further and question the complicity of the discipline of international law in the reproduction of coloniality. The myth of the neutrality of international law feeds into the delusion that international legal academics are all driven by cosmopolitan ideals and remain immune to national interests. How such a cynicism can take hold in a discipline in which the freedom of navigation – one of the foundational concepts of the discipline – was articulated in an advice of the Dutch jurist, Hugo Grotius, to the Dutch East India Company to defend the latter’s rights is hard to understand. What is important to realise here is that like most academic disciplines, contemporary international law is a Western discipline primarily shaped by Western international lawyers. It is not a coincidence that many concepts of international law that give Western countries special privileges, such as the theory of the persistent objector, the doctrines of specially affected states, of the “gouvernement international de fait” and of state contracts, were framed by Western scholars. Likewise, the idea that states that attainted independence as a result of decolonisation had no choice but to accept international law as it was even though they had no opportunity to participate in the making of that law was primarily articulated and promoted by Western international lawyers.It is not a coincidence that many concepts of international law that give Western countries special privileges were framed by Western scholars.

But despite the situational anchoring of Western conceptions of international law, Western textbooks of international law are generally seen as representing not just the Western approaches to international law, but international law tout court. Non-Western textbooks, on the other hand, are systematically portrayed as situated accounts of international law (“Third-World”, “Chinese” or “Russian” approaches to international law). As long as the Western conceptions of international law keep this privileged position, enabling them to claim the “monopoly of the universal” (Pierre Bourdieu), no genuine decolonisation is possible given the interpenetration of knowledge and social/political orders. This situation cannot be remedied simply by giving non-Western conceptions of international law a space or voice within international law academia if “the credibility economy” (Miranda Fricker) that prevails in academia is not radically revisited. In other words, the key question is not “who is entitled to speak?”, but “who should be listened to seriously?” (Gayatri Spivak) when the “academia in the Global North continues to set the intellectual agenda and prescribe the standards and protocols of good scholarship” (B. S. Chimni). The uncomfortable truth, therefore, is that it is not possible to achieve genuine decolonisation without addressing the “colonisation of the minds” (Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o).

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.