Varieties of Decolonisation

It was never any secret that many of the most renowned institutions of higher learning, particularly in Britain and the United States, owe their existence to slaving and colonial fortunes. Nor that the public figures they celebrate in stone, brick and metal, and in a dozen other ways, had owned and traded in slaves, colonised continents, presided over genocidal colonial policies, or been guided by white supremacist beliefs. Yet the Rhodes Must Fall movement that broke through this silence did not erupt in the West, but at the University of Cape Town in 2015, whence it spread to Oxford, thanks largely to South African students connected to the Cape Town protests, before inspiring similar movements at other British and US universities. Black Lives Matter lent fresh momentum to such campaigns and propelled them beyond the walls of academia.

Removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town on 9 April 2015.

Removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town on 9 April 2015.Scholars have likewise long been aware of the parochial nature of the social sciences and the humanities, which offer little unpoliced space for the sensibilities and perspectives of the vast majority of the planet’s inhabitants. The epistemic inequalities they embody and reproduce through their disciplinary and institutional configurations are equally well-known. Inequalities also deform the academic body, which tends especially at the more renowned and better-resourced institutions to be predominantly white, male, and upper-class. Yet no reckoning with the racial, colonial, gender and other forms of bias and discrimination in academia would have been possible, as Black Lives Matter freshly reminds us, without twentieth-century struggles around the world for equality and their growing intensity since the 1950s in the wake of anticolonial movements and the onset of decolonisation.

There is a twofold lesson here. Political struggles and social mobilisations profoundly shape what we study and how. Few influences do more to expand our horizons, and those of our disciplines, than struggles by marginalised and disadvantaged groups for equality, rights and freedoms.Fissures and fractures in postcolonial world-making have a direct bearing on projects for decolonising the world of ideas

This lesson can be useful for navigating the currents of intellectual decolonisation at a time when the air seems so thick with it. It is well to remember at the outset that anticolonial projects and aspirations to decolonise have a long history. Two of the three landmark historical events that arguably ushered in the modern political era, namely the US Declaration of Independence and the Haitian Revolution, were anticolonial. Historians of the late eighteenth-century revolutionary Atlantic continue to bring to light the many ways in which the two revolutions were braided. Yet their starkly contrasting trajectories and fortunes, not to mention the seeming paradox of how relations between Haiti and the United States unfolded over the next two centuries, encapsulate the complex history of anticolonialism and decolonisation.

Anticolonial struggles and decolonisation movements have unquestionably transformed the world. They have, even in their failures, continued to fire our imaginations. Their dreams inspire awe. Yet bracketing the United States and Haiti serves to draw attention to the breadth of anticolonial movements, and the range of experiences, perspectives and agendas they can mobilise or represent. This breadth is what gives anticolonial movements their power and their poetry. However, one consequence of such breadth is that while the possibilities may appear boundless at particular moments, the actual outcomes often reflect a grimmer reality of conflicts within anticolonial movements. Rarely are these conflicts only internal. The colonial power looms large over them, fostering, deepening or leveraging such conflicts to cement alliances with “moderate” anticolonialists, prolong its own influence and embed itself more deeply within postcolonial structures and dispensations. When such conflicts turn violent, the poetry of anticolonialism can yield to an oppressive prose of postcolonial state-making that absorbs and reproduces the “bifurcations” of its colonial progenitor whilst continuing to speak in the tongues of the anticolonial revolution.

Fissures and fractures in postcolonial world-making have a direct bearing on projects for decolonising the world of ideas, academia in particular. Intellectual decolonisation presents a double challenge, on the one hand subjecting white, Western, colonial or other exclusionary knowledge traditions and modes of knowing to critical scrutiny, and on the other recovering and revaluing knowledge traditions and modes of apprehending the world suppressed by colonialism and other forms of domination. Though the former remains daunting, critical approaches developed in the last few decades do at least map some ways to navigate this challenge.

The second challenge is deeper and more complex. There is much greater awareness now of lively knowledge traditions beyond the West, and their inherent dynamism and malleability. While Western interest in the study of indigenous philosophies is far from new, the growing interest of indigenous (i.e. non-Western) scholars in their own societies’ philosophical and intellectual traditions is likely to pose exciting new challenges to disciplinary boundaries and methods. It is also bound to revive thorny questions about meaning, commensurability, and the nature and scales of the universal.Who speaks for (and as) the decolonising subject will be pivotal to democratic struggles for intellectual decolonisation

There are few easy answers to such questions. A partial clue may lie, however, in the domain of representation, which remains in any case an indispensable benchmark for social knowledge. The project to decolonise the world of ideas will be self-defeating if it is not democratic, since it otherwise risks producing new despotisms of thought and belief. Western colonialism was not the first power to suppress other systems of thought and belief, nor is it likely to be the last. India, for instance, has a long history of Brahminical campaigns to erase or absorb resistant belief systems of communities on the margins of the caste or varna order. All major world religions and religions aspiring to that status share similar histories. Yoke them, or other similarly powerful ethnocentric beliefs, to ethno- or religious nationalism and the nation-state, and frame the resulting claims into an anticolonial narrative. Presto, you would have repackaged an exclusionary, majoritarian political ideology as a decolonised belief system well enough, in one recent instance, to dupe an Argentine-American champion of “decoloniality” evidently ignorant of the colonial genealogies of the purportedly countercolonial system of “Indic” knowledge. The moral? Who speaks for (and as) the decolonising subject will be pivotal to democratic struggles for intellectual decolonisation. They will in turn be our best hope for negotiating questions of meaning, commensurability and universality in a respectful spirit in any future democratic republic of ideas.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

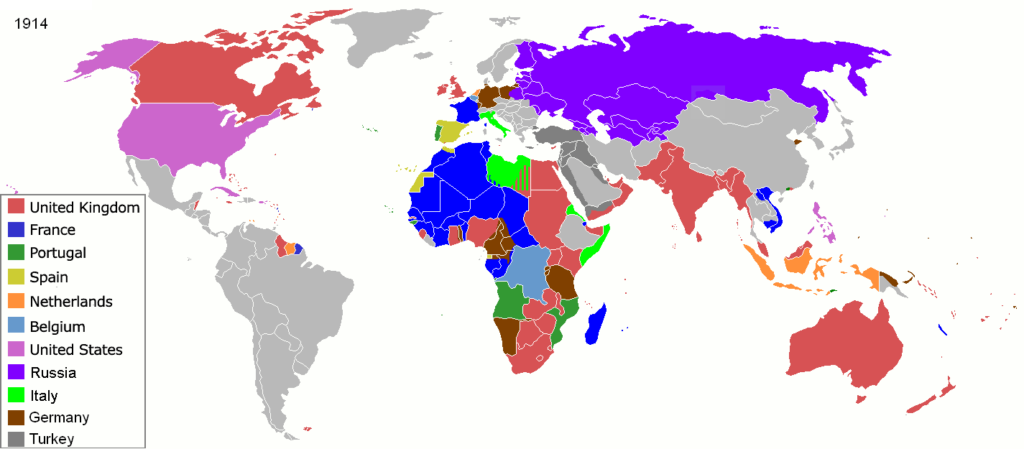

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.