Three Decolonial Questionings of the Digital

In what ways is decolonisation a past questioning the digital? Below, I scratch the surface of three possible answers to this question drawn from the rapidly expanding scholarship on the politics of the digital. They all share an understanding of decolonisation as the ongoing process of dealing with the traces – economic, social, cultural and otherwise – of colonialism in the contemporary world.

Decolonising Digitally

A first answer is that ongoing decolonising processes are afforded by the digital that opens for the possibility of de-colonising through the digital. The digital is a space for nurturing decolonising political strategies and, more than this, to gather support for and build alliances around such politics. Decolonial activism has made astute use of the internet, as illustrated by the Mexican Zapatistas, the Arab springs or the Hong Kong Umbrella movement. In fact, today decolonising processes more frequently than not take place in the expanded place where the “online” and the “offline” are merged and connected. Amazonian Indigenous people are protesting against colonialism online. This said, the “web-romanticism” that once marked understanding of the liberating potential of the internet is gone. The fate of digitally mediated activisms has been sobering. Moreover, the pervasive surveillance, manipulation and exploitation of the digital for personal, political and economic reasons – extending and transforming past colonial practices – are severely limiting the prospects of decolonising digitally from within digital infrastructures. Yet, activists have not relinquished the digital. They have adopted “pragmatic strategies” working with the digital from within rather than criticising it from without. Of course, part of such decolonial activism is directed at the digital realm itself.

Decolonising Digital Infrastructures

A second answer is that the decolonising of the digital has become a core stake for ongoing decolonial processes. The digital is neither a mere tool for decolonial politics nor simply a “platform” where decolonising struggles play out. Rather, digital infrastructures perpetuate the marks of a colonial past. They are made by large public-private, often-military research projects, by the GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) and by an unruly undergrowth of enterprising innovators. They encompass the “Global South” that supplies much of the engineering, labour, data and space for experimenting required for these infrastructures to operate. Moreover, many countries, including China, Iran, Brazil and North Korea, are developing their own digital technologies and asserting their “cyber sovereignty”. However, priorities and control remain overwhelmingly with the “markets” and national security agencies of the “Global North” (the US in particular). The consequences are built into the infrastructures that enshrine the primacy of security and consumerism, visible even in the politics of DAESH recruitment videos. Activists and academics hence point to the significance of decolonising the digital itself. So does Google’s AIUX design team, affirming the import of “redistributions of power” and “broader system change” to achieve “racial equity in everyday products”! In fact, all GAFAM have programmes dealing with the traces of colonialism in the digital that aim to make infrastructures more “inclusive” and “diverse”. Such claims testify to the commercialisation of everything, including revolution. Ironically, the decolonisation of digital infrastructures is pursued not only by radical “cyber activists” or governments in the “Global South” but also by the companies operating these infrastructures.

Decolonising Digital Subjectivities

A third answer is that the decolonising of digital subjectivities has become so fundamental for the ongoing processes of decolonisation that it is now a condition of their possibility. The algorithms sorting, classifying, channelling and modulating data flows are not only shaping the business models connected to personalised advertising practices of companies and the profiling of intelligence or border control agencies but also the gains made from the ransomwares or leaks of the hackers (or information system specialists) who manage to tamper with them. More radically, and in part through these processes, algorithms “make up people”. Can the digital subject (activist or historian of colonialism), marked by data colonialism, speak to articulate it? They are defining for what people experience, learn, think, feel, and so their development, thoughts and doings. They shape their within in a “sticky” way. They enshrine invisibility, bias and stereotypes as Joy Buolamwini problematizes in her work. Moreover, many people connect or export central part of their selves to the digital without. Memory is exported to calendars remembering appointments, the sense of space to apps that calculate routes, the appreciation for wine to wine-tasting apps, the ability to fall in love to dating apps, etc. “Subjectivities” have become digitally mediated and individuals turn into “divididuals” distributed across the digital space. The subjectivities of smartphone-addicted teenagers but also of political activists and scholars are increasingly digital. Historians of decolonisation are no exception. Their sources, tools, publications and scientific exchanges are increasingly digitised. Decolonisation may be a past that keeps questioning us. However, that questioning is not a given. Can the digital subject (activist or historian of colonialism), marked by data colonialism, speak to articulate it? While the answer is uncertain, it is clear that cultivating openings in the design of digital infrastructures is a condition of possibility for this to happen.

These are three obvious, common, ways of connecting decolonising processes and the digital. Obviously much more could (and should) be said about the broader implications of these connections for decolonising politics – and perhaps politics tout court. There is scope for continuing the conversation.

Video | “The Coded Gaze: Unmasking Algorithmic Bias” by Joy Buolamwini

By Joy Buolamwini

Video | “The Shot” by Alessandro Turchioe

Text by Donatella Della Ratta, video by Alessandro Turchioe.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

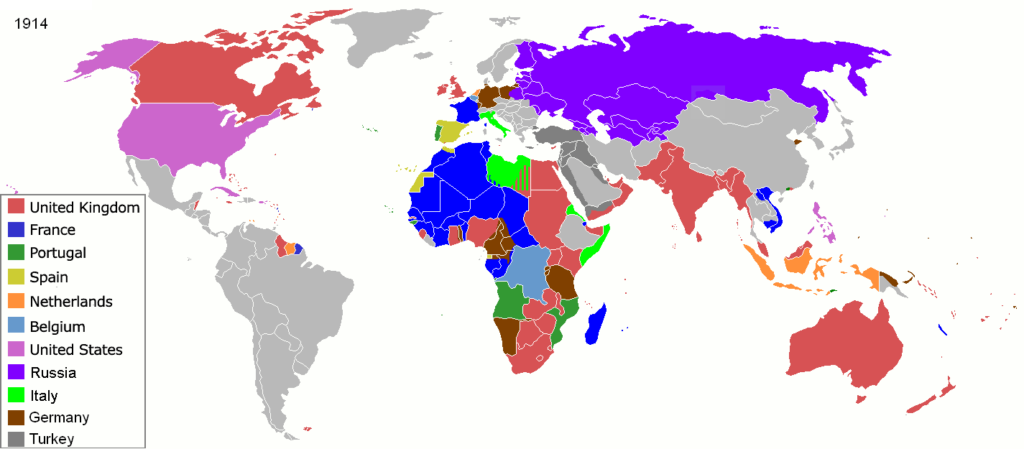

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.