Decolonisation and Regionalism

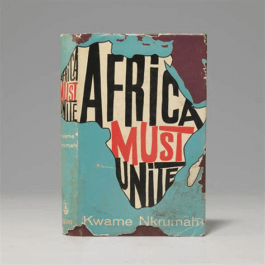

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-jvta-dk42Changing space has long been central to projects of decolonisation. For Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, national independence was only the beginning: overcoming the divide-and-rule of colonial partition meant regional integration on a continental scale.

Nkrumah’s dreams were frustrated in his lifetime. But from Africa to Latin America to Southeast Asia, regional solidarity still holds the promise of prosperity, peace, and the strength to resist neocolonial dependence on the United States, Europe or China.

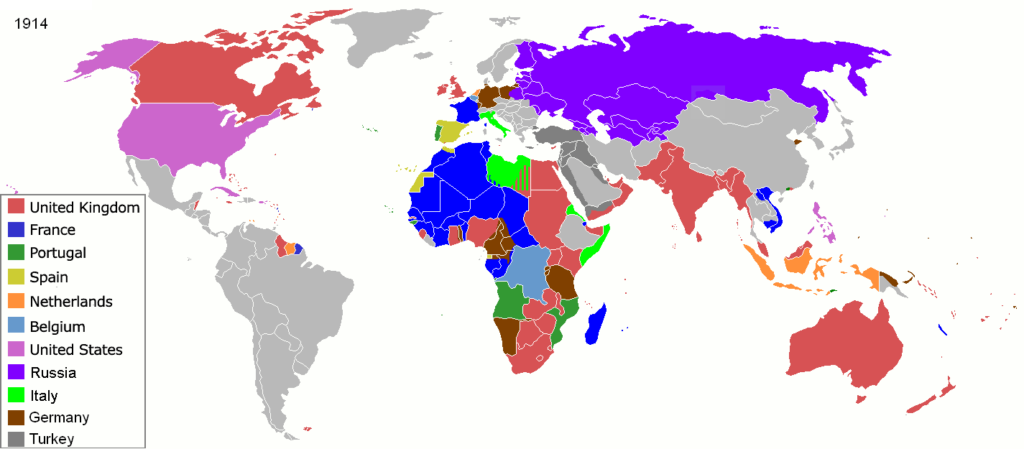

Decolonisation and regionalism have a complicated history, however. Integration was also a priority for Europe at the end of empire, for quite different reasons. “Would it not be a success if we could realise the dream of Eurafrica?” asked Paul-Henri Spaak in 1957. He saw this future in the Treaty of Rome, with EEC affiliation for colonial possessions – regionalism as an alternative to decolonisation, not as a means to achieve it.

But decolonisation is not just about political arrangements. In decolonial thought, it is about knowledge, power, and the material consequences of domination and dispossession. Regionalism is such a body of knowledge. It shapes what regions are, how they function, and what they should be.

The conventional place to start is Eurocentrism: the European Union (EU) is not the model for the world. Amitav Acharya, for instance, argues that the thinking of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on consensus and national sovereignty is more influential than that of the EU. Comparison, however, may still be valid: the great Nigerian historian Anthony Asiwaju has long urged the comparative study of the African Union and the EU, not to measure one against the other but to build a better future for both. It is Europe’s false centrality that matters.

But there are more fundamental questions to face. For one, “region” is a dangerous word. When set against the divisions of national borders, it is self-justifying: it speaks of naturalness, neutrality. It is a good space, the right space, no matter who looks at it or where it comes from.

Colonial ideas of race, civilisation and the orientation of power underpin the conception of continents and world regions: elevating Europe, inventing Africa and creating the Middle East. This makes it something to distrust. Looking at a map, it is hard to miss the colonial heritage of borders. But it is easy to forget the colonial demarcation of other spaces. Imperial languages and infrastructures shape “natural” spaces of cooperation, from East Africa to the Caribbean. And as Edward Said and Valentin-Yves Mudimbe explored, colonial ideas of race, civilisation and the orientation of power underpin the conception of continents and world regions: elevating Europe, inventing Africa and creating the Middle East.

What happens when we denaturalise regions inherited from imperial thinking? The Kenyan scholar Ali Mazrui argued for the “abolition” of the Red Sea. He looked to restore the historic continuities of an “Afrabian” space that was denied by European racial categories. Such spaces have their own historical tensions to confront. But new solidarities could be built on older, suppressed commonalities.

This is about the meaning of space, not just names or boundaries. Nkrumah’s Pan-African dream was not invalid because it accepted the European outline of the continent. “Once the indigenous conquered peoples of the continent choose to retain the term ‛Africa’”, writes South African philosopher Mogobe Ramose, “then they are entitled to give content and meaning to it.”

Is regionalism just a reshuffle of imperial structures, or an opportunity for revolution? Questions of meaning hinge on the nature of power within and without these spaces. This is where the decolonisation of regionalism as knowledge passes onto practice. Can a region such as Europe “manage” its borders without eroding its neighbours’ sovereignty? Can regions built around the hegemony of Germany or South Africa escape internal dynamics of dispossession? Can historically marginalised nations like Haiti or Burundi act as equals alongside their regional partners?

The problem gets deeper when we think about relationships with people rather than between states. Who is regionalism for? Can it restore land to the dispossessed, security to the displaced? To Frantz Fanon (a great believer in the nation), any successor to empire defined by the interests of a national bourgeoisie was a reformulation of colonial domination and dispossession. Is regionalism just a reshuffle of imperial structures, or an opportunity for revolution?

Decolonising regionalism, in any case, goes beyond redrawing the map, or decentring Europe. It is a critical, radical, all-encompassing reformation of the oldest questions: who benefits, who pays, and whose ideas matter.

Walter Mignolo offers “border thinking” as the means for moving beyond Eurocentrism and reactionary nativism in decolonial thought. This means thinking from the borders of territory, knowledge and power, instead of standing in the old centres and studying – looking at, thinking about, doing something for or to – the old margins. Where ideas come from matters. This is a starting point, not an answer.

Perhaps, then, regionalism must be liberated from the grip of conventional economic, political and historical thinking, of the rational actor and the nation-state. In place of trade, imperial heritage or security, can regionalisms emerge from relationships between people and animals, express the true universals of climate crisis or define experiences of space that depart entirely from the premise of territory?

“We are the children of geography and history”, notes Ethiopian philosopher Teodros Kiros, “born to a given race, a given region, at a particular time, in a particular place.” None of these meanings are singular or fixed – not ourselves, our regions, our races, our histories. But all are entangled. Redefining one means redefining the rest. The place where we stand changes the spaces we see around us.

Electronic reference

Russell, Aidan. “Decolonisation and Regionalism.” Global Challenges, no. 10, October 2021. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/10/decolonisation-and-regionalism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-jvta-dk42.This issue has been produced by the Department of International History and Politics in collaboration with the Geneva Graduate Institute’ Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.