Decolonisation: The Many Facets of an Ongoing Struggle

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-17bd-m426Today, we observe a renewed interest in decolonisation in at least three interrelated spheres. First, in the academic world, scholars have opened new areas of research on decolonisation, which is increasingly looked at in historical and comparative perspective; more broadly, a new generation of scholars has called on all disciplines to reflect upon their teaching tools, research methodology and epistemology to re-examine the traces of their past association with colonial practices and perspectives. Second, in the world of international governmental and non-governmental organisations, professionals in fields such as humanitarian action, global health and development have started to reconsider their way of working by examining the persistent inequalities between practitioners from the Global North and South. Third but not least, social movements like Black Lives Matter or Rhodes Must Fall have changed the lenses through which the general public sees the legacy of colonialism in Western societies, where colonial artefacts are still visible and often celebrated in street names, statues or museum objects. In parallel to changing perceptions of how former empires have treated their past, social movements have helped place on the political agenda the urgent need to challenge the cultural codes and social practices that are responsible for systemic racism as well as for more subtle forms of discrimination.

Still, the novelty attributed by certain political commentators to the latest discussions on decolonisation should not be taken at face value. Lingering Eurocentrism, the continued oppression of indigenous people in the name of theories of racial supremacy, the pitfalls of universalism, the persistent materiality of colonialism or, more generally, the need to confront the cruel side of Western modernity: these have all been discussed by scholars and activists since the onset of decolonisation – and before.

The discussion continues today, as scholars take issue with the notion that our societies have entered a “postracial” age, a utopian notion proposed by certain cosmopolitan American philosophers after Barack Obama’s first election to the US presidency, and whose flaws were revealed as soon as Donald Trump ran for President and was elected.

Many voices now emphasise the need to develop an intersectional approach to research methodologies that takes into consideration how race, gender, nation or class interplay in granting legitimacy (or not) to a variety of knowing subjects and knowing practices, so as to avoid reproducing asymmetries of power that are too often left unquestioned even by progressive ideologies. These debates are important, as they demonstrate an increased sensitivity to key epistemological issues associated with the legitimate questioning of a long-established white privilege. However, these new forms of questioning may appear less original if one recalls that some disciplines have long drawn, for example, upon feminist reflections on the situatedness of our viewpoints, or upon international law and anthropology when the latter questioned the universality of human rights and the importance of their cultural embeddedness in national or regional (African, Asian…) viewpoints. Or indeed when they have addressed issues such as the speed at which environmental measures should be adopted by the developing vs. the developed world. That the media and political conversation fails to register the historical depth of these debates is a sign of a political amnesia that may contribute to delegitimising the academic scholarship that has accumulated on these topics over the last 50 years.

Historicising decolonisation

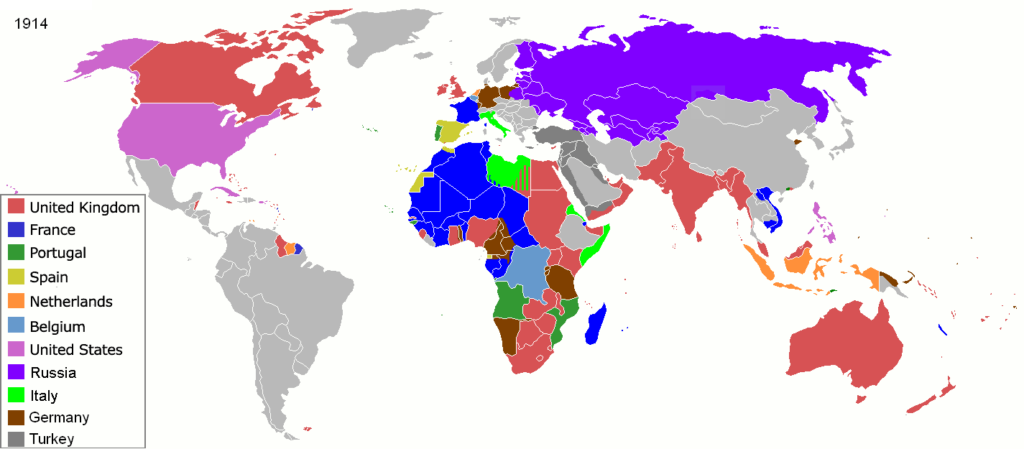

This thematic issue of Global Challenges seeks to unpack the variety of such perspectives on decolonisation, from the point of view of different disciplines and research traditions. First of all, the contributions stress that colonialism is a complex and diverse phenomenon, and one that is not the sole prerogative of the West. It is tied to a multiplicity of historical experiences, actors and contexts, which should be taken into account when seeking to understand the diversity of claims and experiences behind the unified calls to decolonise today’s world. The experiences of indigenous populations in settler colonial contexts and their claims for decolonisation, for example, differ markedly from those of Northern Africans colonised by the French, English or Italian empires or from those of students experiencing discrimination in Western universities today. Second, colonialism needs to be understood in terms of historical continuities and ruptures. From a long-term perspective, the history of colonialism predates the Western nation-state, and decolonisation should not be read exclusively as the story of the nation-state and the rupture of independence; alternative geographic spaces and political constructs — empires, regions, continents or more local entities — are equally relevant to colonialism, decolonisation and its legacies.

… and its inherent risks

Current calls for decolonisation point to a variety of pathways towards effective decoloniality. One approach views decolonisation in open-ended terms, aiming at epistemological inclusivity and criticising the West without rejecting it outright. It insists that modernity itself is a global phenomenon to which the Global South has contributed significantly. Indeed, many allegedly Western concepts, values and educational models have been shaped by contributions from “non-Western” societies and have long since acquired a global life of their own. In a worldwide context of interdependence — albeit frequently on highly asymmetrical terms — efforts to single out in global processes what is specifically associated with white, Western privilege could not only prove ineffective but also counterproductive; they could instead end up endorsing reconstructions of history that incorrectly put the West at their centre. Thus, decolonising knowledge could mean recovering the complex, hybrid and plurivocal nature of important concepts that were unfairly appropriated by Western scholars, especially during the colonial era when racist ideologies allowed a substantial amount of intellectual theft.

At the same time, other scholars point out that the decolonisation of knowledge may remain incomplete if it fails to make a clean break with existing biases. A wide gap may persist between the theoretical sophistication of scholarly calls to decolonise the canon and its actual decolonisation on the ground, considering the strength of academic resistance against any challenge to its canonical constructions. Calls for decoloniality may then only be heard when expressed by Western intellectuals, who use Western tools and methodologies such as philosophies of deconstruction and Marxism, but refrain from applying them to their own positionality or to the alternative societal models they defend. The decolonisation of our current disciplines is at risk of being conducted only superficially, as an exercise in tokenism. Worse, it may fall prey to subversion and reappropriation by old-fashioned academic hierarchies; this is often the case when scholars confuse positionality, which is fluid and contextual, with fixed attributions of ethnicity or gender. A superficial approach to decolonisation then is not without its own set of risks, as it may nurture polarisation on a global scale and entrench an overtly deterministic worldview that precludes more open-ended outcomes.

If subverted in this way, a call to decolonise knowledge is at risk even of being used for the precise purposes that it seeks to combat. A subversion of this kind would be all the more problematic if it were used by nationalist or neo-imperial ideologues in their campaigns against human rights and minorities, as is currently the case, for example, in Europe, China, Russia and India. Concern for historical truth is not an issue for many revisionist ideologues, such as those in Europe who would claim that Europeans will themselves soon need to be decolonised from a reverse form of colonialism. To some extent, there is thus a risk of seeing calls for decolonisation misappropriated in justification of uncompromising forms of nationalism or a renewed racialism that could well give rise to new forms of exclusion, intolerance and discrimination.

Levelling the playing field

This issue of Global Challenges aims, therefore, to put decolonialisation into historical perspective and to provide fresh analytical insights into its epistemologies and methodologies, as well as into its practical applications. By gathering contributions from scholars of decolonisation whose research interests range from the decolonisation movements of the 1960s to contemporary processes and epistemes that remain permeated by “coloniality”, decolonisation is treated here as a mode of action, a modus operandi for finding expression – with varying degrees of success – in such varied fields as humanitarian action, global health or education. It also enquires into productive ways to diversify existing knowledge systems, support intercultural dialogue and foster new ways of advancing social and historical justice through innovative approaches to decolonisation.

As many of the contributors emphasise here, the “legacy of colonialism” still prevails in many non-colonial contexts, where it helps to perpetuate oppression and exploitation. The priority in academia today lies in epistemological decolonisation, i.e. decolonising knowledge, institutions, habits and languages. Academia has long explored the nexus between power and knowledge, denouncing the noxious effects of Western universalism. Today, the emphasis is on decolonising curricula by addressing omissions and silences, and on furthering alternative ways of knowing by restoring the epistemic authority of marginalised knowers and their knowledge systems. This is now a matter of urgency in academia, whose boundaries have been seriously challenged by the recent rise in racism and hate speech against scholars accused of “Islamo-leftism”. These bouts of racial hatred are particularly difficult to fend off in the digital realm, where social networks are used by propagandists to create lists of decolonial scholars with whom they refuse to debate, but whom they insult without suffering the consequences.

Confronted by such challenges, decolonial activists and scholars have embraced new, transversal forms of mobilisation, associating race and coloniality with gender, environment and class. By doing so, they have joined forces with other rights movements, deconstructing, unlearning and exposing narratives rooted in phallocentric and culture-blind (neo)colonial rationales. Their end goal is an international decentring and/or recentring of existing power relations and structures, through the creation of a level playing field where voices that have hitherto been silenced can be taken seriously and remain audible over time. As such, they have also turned the digitalisation of academia into a resource rather than simply suffering from its abuses.

Driving the decolonial agenda, addressing its traumatic legacies and memories, defying epistemic imbalances and integrating new voices have thus been considered necessary first steps towards decolonisation. However, to move towards a more just and equitable future, more needs to be done. Most notably, efforts are required to devise new ways of living together globally based on new paradigms and also, perhaps, novel types of universalism. What is needed, precisely, are new ways of conceiving the relationships between communities and cultures that overcome not just the pitfalls of Western Eurocentrism qua cosmopolitanism, but also the conceptual frameworks that otherwise are at risk of perennating unequal relationships. To move towards a more diverse, open-ended and constructive future, new categories and epistemologies need to be invented — or old ones reinvented — that overcome the current trend towards political polarisation, cultural hermetism and identarian closure. How this is to be achieved remains uncertain and raises many issues. Key ingredients to such a reconfiguration would certainly include bottom-up dynamics, intercultural exchange and constructive dialogue. While deconstructing is difficult, constructing a new paradigm is even more arduous. But it is a necessary challenge, which this varied range of contributions tries to take up.

-

1

Varieties of Decolonisation

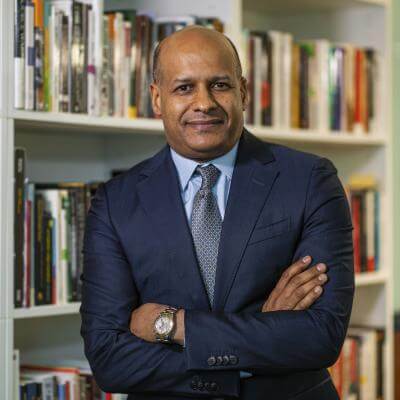

Varieties of DecolonisationSince 2015, leading universities around the world have come under increasing pressure to reconsider their colonialist legacy. Situating contemporary movements such as Rhodes Must Fall within a long history of anticolonial projects, Gopalan Balachandran examines the epistemic inequalities still inherent in the social sciences and humanities, and explores the challenges inherent in attempts to decolonise the world of ideas.

-

2

Decolonisation: Too Simple a Term for a Complicated History

Decolonisation: Too Simple a Term for a Complicated HistoryFrequently, the end of colonial rule has not resulted in a radical break between a former colony and its former metropolis. The dominant social classes have likewise often extended their dominance after the end of occupation. Analysing the continuities and discontinuities after the withdrawal of a colonial power, Jean-François Bayart reviews the diverse history of decolonial experiences around the world.

-

3

Decolonisation and Regionalism

Decolonisation and RegionalismFrom Africa to Latin America to Southeast Asia, regional solidarity represents a potential alternative to a neocolonial dependence on the West or on China. Starting from the regional aspirations of the decolonisation project, Aidan Russell examines the complicated history of decolonisation and regionalism, and the potential for regionalism ultimately to redefine the relationship between people and territory.

-

4

Decolonising International Politics

Decolonising International PoliticsThe study of international politics today remains dominated by Eurocentric positions, with a focus on analysing interactions in terms of power, sovereignty and capital. Arguing that Postcolonial Studies is often delegitimised in favour of a handful of “core” perspectives, Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou calls for a more universalist, nomothetic approach to the study of international affairs.

-

5

Decolonising the Global

Decolonising the GlobalTaking as her starting point the conceptual importance for globalization theory of the Earthrise images from the Apollo 8 space mission, Carolyn Biltoft analyses the ethics of today’s global environmentalist movement. She urges a note of caution, however, suggesting that discourses of ecological unity are often subject to the same Eurocentric assumptions that undergirded imperialism to begin with.

-

6

Decolonisation and International Law

Decolonisation and International LawInternational law has long had an ambiguous relationship with the colonial enterprise, at once enabling colonial practices and subsequently facilitating the independence of many former colonies. Fuad Zarbiyev examines the tensions in this relationship as well as the implications of the continuing dominance of Western approaches to international law today.

-

7

Gender and Decolonisation

Gender and DecolonisationWriting, fighting or protesting, women around the world were highly involved in the anticolonial movements of the 20th century. More recently, however, some of the spaces created by these anticolonial movements have closed, leading to a paradoxical reduction in freedom. Highlighting the continuities with the past that remain even after decolonisation, Nicole Bourbonnais explores the emancipatory project of decolonial feminism.

-

8

Decolonisation and Humanitarianism

Decolonisation and HumanitarianismAt least as far back as the Spanish colonisation of the Americas, humanitarians accompanied the colonising armies, distributing charity and helping to establish the state. Taking as his starting point the sometimes ambiguous role of humanitarians in the colonial enterprise, Davide Rodogno argues that decolonisation has not resulted in fundamental changes to the paradigm of international humanitarianism.

-

9

Decolonisation and Global Health

Decolonisation and Global HealthWith programmes such as the elimination of yellow fever in Panama in the early 20th century, global health has its origins in the service of colonial empires. Examining the asymmetrical nature of today’s global healthcare provision, Tammam Aloudat, Dena Arjan Kirpalani and Meg Davis argue that global health continues to employ many of the methods that have plagued it from the outset.

-

10

Decolonising Education

Decolonising EducationEducation is generally seen as a meritocracy, with the potential to reduce social inequality and promote democracy. However, argue Moira Faul and Oakleigh Welply, educational institutions tend to promote a Western canon of knowledge, at the expense of other knowledge systems and voices. This bias requires “decolonisation”, including revised curricula and more egalitarian partnerships with the Global South.

-

11

Three Decolonial Questionings of the Digital

Three Decolonial Questionings of the DigitalFrom Hong Kong to the Amazon, decolonising processes today most often happen in the expanded place where the “online” and “offline” are merged. At the same time, pervasive surveillance and manipulation limit the scope for digital decolonisation. Anna Leander explores the challenges for decolonisation in the digital space, as well as the importance of decolonising the digital space itself.

-

O

Selected Publications from the Graduate Institute about Colonisation and Decolonisation

Selected Publications from the Graduate Institute about Colonisation and DecolonisationA quick look at the Graduate Institute academic production dealing with decolonisation issues.

Electronic reference

Mallard, Grégoire, Dominic Eggel, and Marc Galvin. “Decolonisation: The Many Facets of an Ongoing Struggle.” Global Challenges, no. 10, October 2021. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/10/decolonisation-the-many-facets-of-an-ongoing-struggle. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-17bd-m426.This issue has been produced by the Department of International History and Politics in collaboration with the Geneva Graduate Institute’ Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.