Decolonising Education

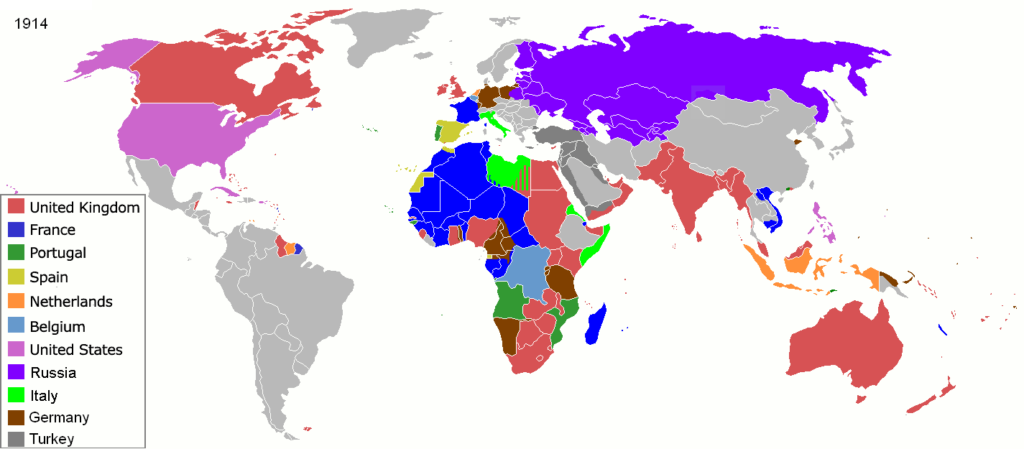

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-k69g-a045Colonialism and education are closely interlinked. The role of education in colonialism is undeniable. Historically, education systems were used – and abused – in efforts to control colonies. In 2021, African children are taught history of the global North and tested to Northern “standards”, while children in the North are not systematically taught African history nor assessed against African knowledge systems. The content and practices of education have colonised minds: knowledge systems developed in the global North, based on an ideal rational scientific model, dominate educational thinking and practices.[1] The dominance of Northern “standards” permeates education, both internationally through unequal comparisons (such as PISA) and domestically through the reproduction of injustice and oppression within educational systems,[2] to the detriment of other knowledge systems and the peoples who embody them.[3] Thus, the African, Asian and Latin American women and men who defend their societies and land are described in Western media as “environmental activists”, ignoring the more holistic conceptualisation of the environment, society and economy that informs their ontologies, epistemologies and affective systems. Rather than enabling legitimate concerns to become dominant, that which dominates has become legitimated.

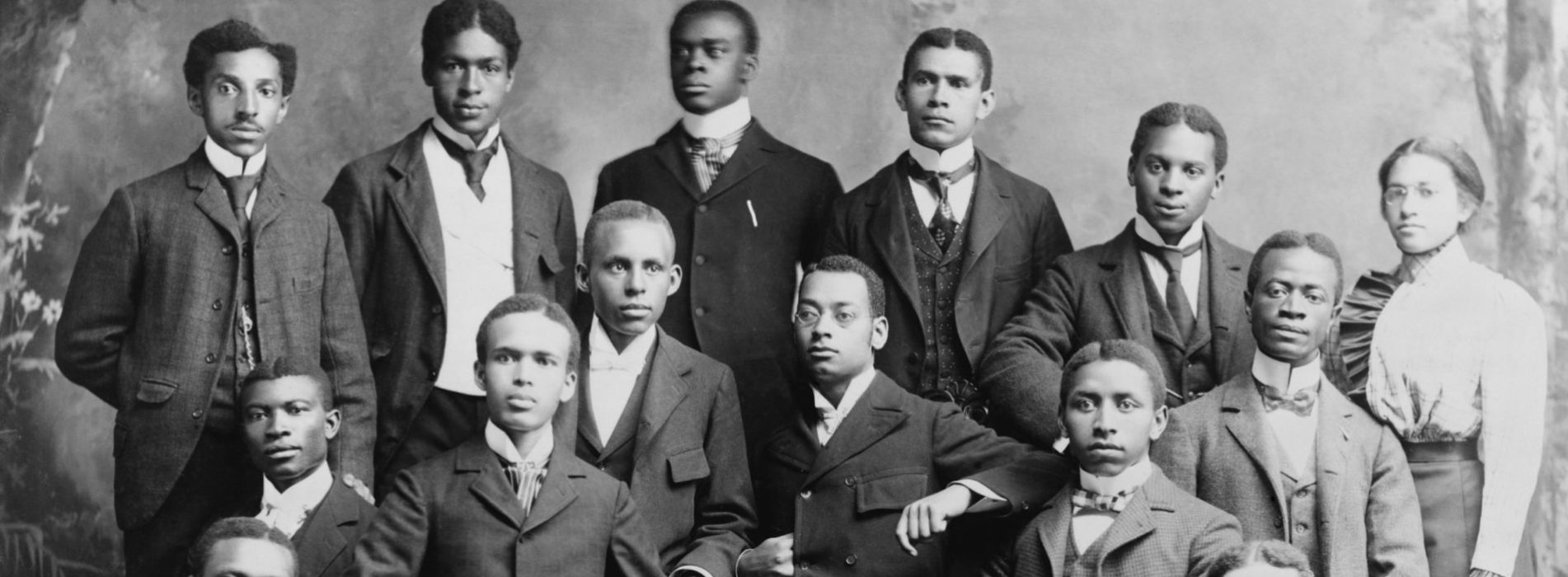

Calls for decolonisation stem from lived experiences of inequalities that reflect historically uneven power relations and legacies of colonialism. Hence, decolonising education – as other sectors – demands recognising a historically specific set of colonial power relations, and how they continue to play out in structures, institutions, relations and processes today. Academic research enables tackling and theorising continuing inequalities by situating lived experiences within wider structures and discourses of oppression, and showing what is missing from the usual stories we tell ourselves.[4] It is no accident that one of the signature moments that popularised decolonisation took place in educational settings: from Grahamstown, South Africa to Oxford, UK, the Rhodes Must Fall movement was inspired and invigorated on university campuses.

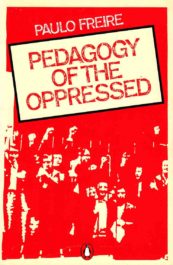

What does decolonisation mean for education? Education has long been idealised as a transformative system that can address social inequalities and promote democracy. Yet, in practice, education is also a site of social reproduction which upholds one “canon” of knowledge to the exclusion of others. Decolonising education therefore requires interrogating historical legacies and dominant forms of knowledge, as well as how they contribute to favouring certain groups, countries or cultures over others. The educational philosopher Paulo Freire, for example, promoted teaching critical literacies that would enable communities to problematise and question their societies – to read the world as well as the word – thereby allowing for the transformation of education, peoples and societies.[5]

Such learning would be embedded in local realities, rather than notions of “universal” (read Western) “standards”. Decolonising education would therefore provide more relevant learning experiences for our students, and enable education to fulfil its potential for transformation.

We have identified five interrelated areas that require a decolonising approach in education: teaching, research, institutions, estates and reparations.

Teaching: Decolonising teaching notably includes questioning what we currently leave out of students’ education in terms of knowledge; changing pedagogies to be more inclusive, for example through open-ended, multilingual and multicultural practices; revising curricula to include historically excluded stories from marginalised communities (because of dis/ability, race, sexuality or otherwise); bringing students’ cultures, languages, gender and perspectives into classrooms; promoting respect beyond tokenism; and decolonising assessment by allowing different forms of knowledge and expression beyond testing against so-called “standards”.

Teaching: Decolonising teaching notably includes questioning what we currently leave out of students’ education in terms of knowledge; changing pedagogies to be more inclusive, for example through open-ended, multilingual and multicultural practices; revising curricula to include historically excluded stories from marginalised communities (because of dis/ability, race, sexuality or otherwise); bringing students’ cultures, languages, gender and perspectives into classrooms; promoting respect beyond tokenism; and decolonising assessment by allowing different forms of knowledge and expression beyond testing against so-called “standards”.

Research: How we conduct research, and how we mentor students to prioritise certain types of research over others,[6] is deeply entangled with a colonial past that marginalised or silenced a large number of non-Western knowledge systems and ways of theorising.[7] Moreover, conducting research with the South requires nurturing meaningful and egalitarian partnerships, and avoiding extractive research practices that echo colonial era exploitation of raw materials (data) from colonies, while the added value of manufacture (or analysis) is carried out in institutions in colonising countries.[8]

Institutions: The imperative is to examine and address the ways in which the behaviours of faculty, students and staff feed into the perpetuation of historic inequalities, as well as identifying processes that may change these behaviours. Unequalising institutional structures and practices of recruitment, promotion and workload also require critical examination.

Estates: Decolonising estates requires scrutinising the names of the buildings, statues and portraits on campuses, and reassessing institutions’ – sometimes vast – investment portfolios and how they perpetuate the immiseration of populations in the Global South, whether through social, economic or environmental exploitation.[9]

Reparations: Institutions must examine the historical origins of the wealth that allowed their creation and flourishing, and take action to advance more justice-based outcomes. Actions would include integrating more students and faculty from communities that have been historically marginalised, such as at Georgetown University where scholarships were recently granted to descendants of the slaves sold to establish the university.

The primary reason to decolonise education is, simply, justice. Colonialism led to inequalities between countries, and between groups within countries. The purpose of decolonisation efforts is not to make people feel guilty, but to better understand the politics and power dynamics of what we do and how we do it; of where and how knowledge is produced and legitimated, by whom, and with what effect. Decolonisation requires us to take seriously the power relations that shaped the current world order and continue to sustain it. Decolonisation provides us with a more honest and evidence-informed appraisal of colonial pasts, and how they continue to be entangled with our present. Decolonisation crucially addresses what can we do to allow education to live up to its potential as a transformative crucible for individuals and societies. It is difficult to justify ignoring the perpetuation of inequalities forged in the colonial era. On the contrary, it is time to collaborate to build and foster decolonial educational practices.

Electronic reference

Faul, Moira V., and Oakleigh Welply. “Decolonising Education.” Global Challenges, no. 10, October 2021. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/10/decolonising-education. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-k69g-a045.This issue has been produced by the Department of International History and Politics in collaboration with the Geneva Graduate Institute’ Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.