Gender and Decolonisation

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-c40r-me68The history of decolonisation in the twentieth century is often told as a history of “Great Men”: of Franz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, Mohandas Gandhi, Ho Chi Minh. There is no shortage of male thinkers and leaders from which to draw inspiration as we explore the continuing relevance of anticolonial critiques and movements to contemporary life. But if we fail to also recognise the historical contributions of women and of feminist thought, we miss an opportunity to take this discussion even further, to capture an even broader emancipatory vision from the past, for the future.

1920s–1970s: the gains of decolonisation for women

Women were everywhere involved in the anticolonial movements that peaked across Africa, Asia and the Caribbean from the 1920s to the 1970s. They led strikes, gave speeches, marched, wrote articles, engaged in armed combat, supported guerrilla armies, organised protests, maintained boycotts, reorganised their home lives to support nationalist causes. Some – like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Bibi Titi Mohammed and Djamila Boupacha – became well-known figures in their own right. Many more laboured behind the scenes, doing the background organisational work that made the Great Men’s speeches and mobilisations successful. Their names may be lost to the historical record, but their contributions were foundational. As much as we are drawn to narratives of singular, charismatic leaders, it is this day-to-day labour that actually makes a movement successful.[1]

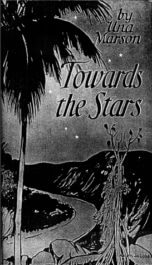

Like men, women participated in these struggles for a variety of reasons. Some came to decolonisation movements through their prior connections to socialist, pan-Africanist, labour or radical organisations; others were caught up in the momentum, fed up with exploitation under colonial rule and seeking something new. Some had explicitly feminist visions of decolonisation. Women like Una Marson, Claudia Jones and Paulette Nardal, for example, wrote brilliant analyses of the intersections between colonialism, class, race and gender in the 1930s and 1940s, long before the theoretical framework of “intersectionality” became popularised. Their work still reads as insightful and relevant today.[2]

As these actors recognised, if colonialism in the twentieth century was a project of economic and political domination, it also had profound social implications. Slavery and forced migration tore families apart; new systems of labour and patriarchal policies entrenched already existing inequalities or created new ones; Victorian-era laws criminalised behaviour that fell outside of strict sexual and gender norms. While some imperial governments made gestures towards women in the dying days of empire – instilling women’s suffrage or creating maternal health programmes – these generally proved piecemeal: too little, too late. Moreover, colonised women questioned whether policies and programmes designed in the metropole – either by male colonial officials alone or with the help of white European “sisters” – could really address their complex concerns. In 1934, for example, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur critiqued the way British feminists dominated the debate over women’s suffrage in India, noting that Indian women’s own voices were like “a cry in the wilderness. … It all seems so tragic that we should say these things again and again only to be told that ‘we know much better than you’. Why, then, ask us ever to give an opinion?”[3]

Several male nationalist leaders recognised these frustrations and attempted to tap into women’s activism. Gandhi situated women at the core of non-violent resistance, Patrice Lumumba argued that women’s education was key to societal progress, Julius Nyerere called for women’s freedom. As gender politics became nationalised, new spaces were opened up to discuss everything from bride price to birth control. Far from side issues, women’s rights and gender relations became hotly contested subjects. As Luise White notes, for example, the Kenyan Mau Mau “issued many more statements about the nature and proper organisation of marriage than it did about land or freedom”.[4]

Postcolonial or Recolonial Times?

This attention during decolonisation struggles led to practical gains for women in many newly independent states, including the creation of state apparatuses and/or social programmes that had beneficial impacts on women’s lives. But many women found themselves disappointed with the overall state of postcolonial affairs. As nationalist leaders shifted from fighting the state to being the state, some of the spaces created by decolonisation movements were closed. Many state women’s ministries/bureaus were marginalised or defunded over time; former combatants struggled to re-integrate, their once praised role in armed battle now seen as a form of gender deviance; female activists were told to return to the home and focus on reproducing the new nation. Sexual expression and sexual minorities became targets of state repression in a number of contexts, seen as threats to the postcolonial order. M. Jacqui Alexander has described this as a process of “recolonisation”, in which “the neocolonial state continues the policing of sexualised bodies … as if the colonial masters were still looking on”.[5]

Life after formal political decolonisation has also continued to be shaped for many by the continuation of imperialist structures in multiple forms. Continuities can be found, for instance, in the domination on the international stage of former imperial powers, the legacy of centuries of lopsided economic policies, and the privileging of Western knowledge and experiences. Indeed, while denouncing the practices of their own states, activists and scholars have challenged the assumption that formerly colonised countries can “catch up” with the “developed” world by adopting their gender norms, feminist theories or models of sexual rights activism. Vanessa Agard-Jones, for example, critiques the way that French gay rights activists “unwittingly support the mapping of a development teleology on France’s Caribbean territories,” labelling them as less “modern” and positioning themselves as “saving” local gay people in a way that echoes colonial narratives and reinforces hierarchies.[6]While denouncing the practices of their own states, activists and scholars have challenged the assumption that formerly colonised countries can “catch up” with the “developed” world by adopting their gender norms, feminist theories or models of sexual rights activism.

Feminist critics like Agard-Jones and Alexander have thus called for a vision of decolonisation at once more contextualised and more expansive, firmly rooted in local experiences but “imagined simultaneously as political, economic, psychic, discursive, and sexual”.[7] One could also turn to the work of Uma Narayan, Amina Mama, Sara Ahmed, Patricia Hill Collins, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Sonia Corrêa, Heidi Safia Mirza, Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Sylvia Tamale, Gloria Wekker and Rosamond King… to name only a few. This rich literature should be seen as crucial for anyone interested in decolonisation: what it has meant, how it has been limited, and what it might entail.[8]

These histories and perspectives are relevant not only for those who live in countries that experienced colonialism and political decolonisation directly in the twentieth century. We all carry the baggage of the imperial past, which continues to affect the way we see others, organise our societies and regulate our intimate lives. The emancipatory project of decolonial feminism provides a way of understanding this history, deconstructing its legacies and refashioning a more just and liberating world for all.

Electronic reference

Bourbonnais, Nicole. “Gender and Decolonisation.” Global Challenges, no. 10, October 2021. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/10/gender-and-decolonisation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-c40r-me68.This issue has been produced by the Department of International History and Politics in collaboration with the Geneva Graduate Institute’ Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.

Video | Decolonising Knowledge: A Historical Perspective from Socio-Anthropology – Prof. Shalini Randeria interviewed by Prof. Grégoire Mallard

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Video | A Brief History of Decolonisation by Prof. Mohamedou

The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Décolonisation et impacts institutionnels en Afrique, par le prof. Eric Degila

Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Le colonialisme vert, par le prof. Marc Hufty

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the University Space, by Gaya Raddadi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonisation and International Organisations, by Prof. Julie Billaud

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Peuples autochtones et décolonisation en 2021, par la prof. Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Podcast | Decolonising the Psyche, Prof Mischa Suter

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

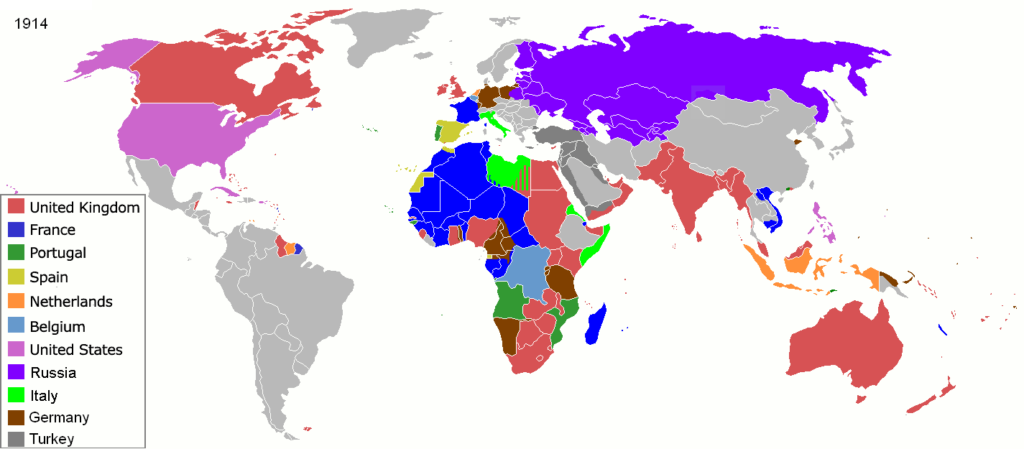

Box | Les empires secondaires de Sa Majesté la reine d’Angleterre

Le Raj victorien, instauré sur les décombres de la compagnie à charte de l’East India Company, a pris la forme d’une vice-royauté qui ne dépendait pas du Colonial Office à Londres et administrait la souveraineté britannique en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est à partir de New Delhi. Dans l’entre-deux guerres, la moitié des fonctionnaires du Civil Service étaient Indiens. Mais, dès les années 1920, la Grande-Bretagne renonça à l’idée d’une citoyenneté impériale digne de ce nom dont les Indiens eussent été les grands bénéficiaires, forts de leur prééminence non seulement en Asie du Sud et du Sud-Est mais aussi en Afrique australe et orientale, ainsi que dans le golfe Persique. Soucieuse de «britannifier» l’Empire, craignant la montée du nationalisme hindou, soumise à la pression des White Settlers, s’employant à coopter des auxiliaires autochtones, ayant renoncé au «travail contractuel» (indentured labor) qui avait envoyé des sujets du sous-continent indien en Afrique, dans le Pacifique et dans les Caraïbes, se refusant à ériger le Raj en dominion alors que les White Dominions connaissaient une ascension impressionnante, l’Angleterre, qui avait déjà renoncé à instaurer la domination de ce dernier sur la Mésopotamie et le Tanganyika, déçut définitivement ses espérances coloniales et les rabattit sur la revendication de l’indépendance qu’incarnera Gandhi, assez tardivement converti au nationalisme.

L’Égypte, de 1882 à 1914, fournit un autre cas d’empire-gigogne. Investi par le sultan ottoman, son pacha – souverain de fait, héréditaire depuis 1841, et pourvu du titre de khédive à partir de 1867 – fut soumis à la suzeraineté du Royaume-Uni à partir de 1882 et partagea alors avec celui-ci la domination coloniale du Soudan, conquis dès 1820. De la sorte, le Soudan est bel et bien une postcolonie, si l’on accepte le terme, et ce à double titre: par rapport à Londres, et par rapport au Caire. Son histoire contemporaine a démontré que le «néocolonialisme» égyptien était aussi virulent que le britannique, si l’on en juge par ses ingérences dans les affaires de Khartoum. Par ailleurs, la conscience nationaliste égyptienne, antibritannique, fut compatible avec des sentiments de loyauté à l’égard du sultan, ou peut-être plutôt du calife ottoman, jusqu’à la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Le cas le plus intéressant de ces constructions impériales baroques est peut-être celui de l’Afrique du Sud, du fait de l’antagonisme entre les Boers et les Anglais et de l’apartheid qu’institua son architecture composite. La domination britannique se superposa à la colonie hollandaise du Cap et entraîna l’exode d’une partie des Afrikaners à l’intérieur des terres en provoquant in fine le combat fratricide – du point de vue de l’impérialisme européen – entre les deux éléments principaux de la Whiteness. L’objectif de la Grande-Bretagne était de garder le contrôle d’une région dont le potentiel économique et les ressources minières ou agricoles paraissaient énormes, et d’éviter en conséquence la constitution d’États-Unis d’Afrique du Sud qu’auraient dominés les Afrikaners. En 1910, il en résulta l’Union d’Afrique du Sud (Union of South Africa, en français Union sud-africaine) : un régime national de ségrégation raciale dans une économie capitaliste à la fois protectionniste et intégrée au marché mondial, que finit par gouverner et définir l’élite politique des Boers vaincus militairement, par le biais du régime parlementaire, et doté d’un statut de dominion de Sa Majesté (jusqu’en 1961). Mais l’histoire ne s’arrêta pas là. Outre la surexploitation, la dépossession et la relégation raciale qu’elle imposa aux peuples indigènes, elle se traduisit par un afflux de ressortissants du sous-continent indien – les Bataves avaient déjà importé des esclaves malais au Cap –, de réfugiés ou d’immigrants économiques d’Europe orientale, centrale et méridionale qui voulurent profiter du boom minier et firent de l’Afrique du Sud un tremplin pour pénétrer l’Afrique australe et centrale, de Portugais soucieux de s’enrichir mais aussi de fuir les incertitudes de l’accession du Mozambique voisin à l’indépendance. Dans le même temps, l’Afrique du Sud était devenue elle-même une puissance coloniale en ayant obtenu le mandat de la Société des nations, puis la tutelle des Nations unies sur le territoire allemand du Sud-Ouest africain (l’actuelle Namibie), et un hégémon régional en intervenant plus ou moins ouvertement dans les pays voisins, en particulier en envahissant l’Angola pour lutter contre le MPLA aux côtés de l’UNITA dans la foulée de la décolonisation portugaise. L’autre face de la combinatoire impériale fut celle des forces anticoloniales. Non sans éviter leurs propres inimitiés complémentaires qui néanmoins n’égalèrent jamais les contradictions fratricides du mouvement communiste en Indochine, le MPLA, la SWAPO et l’ANC – les trois principaux mouvements de libération nationale en Afrique australe – firent plus ou moins front commun contre leurs adversaires locaux et contre l’apartheid sud-africain et rhodésien en bénéficiant du soutien diplomatique ou militaire, parfois ambigu, des «pays frères», la Zambie, la Tanzanie, le Mozambique (à partir de 1975) et le Zimbabwe (à partir de 1980).

Il va de soi que la problématique de la décolonisation n’a pas été la même d’un «empire secondaire» à l’autre.

Jean-François Bayart.